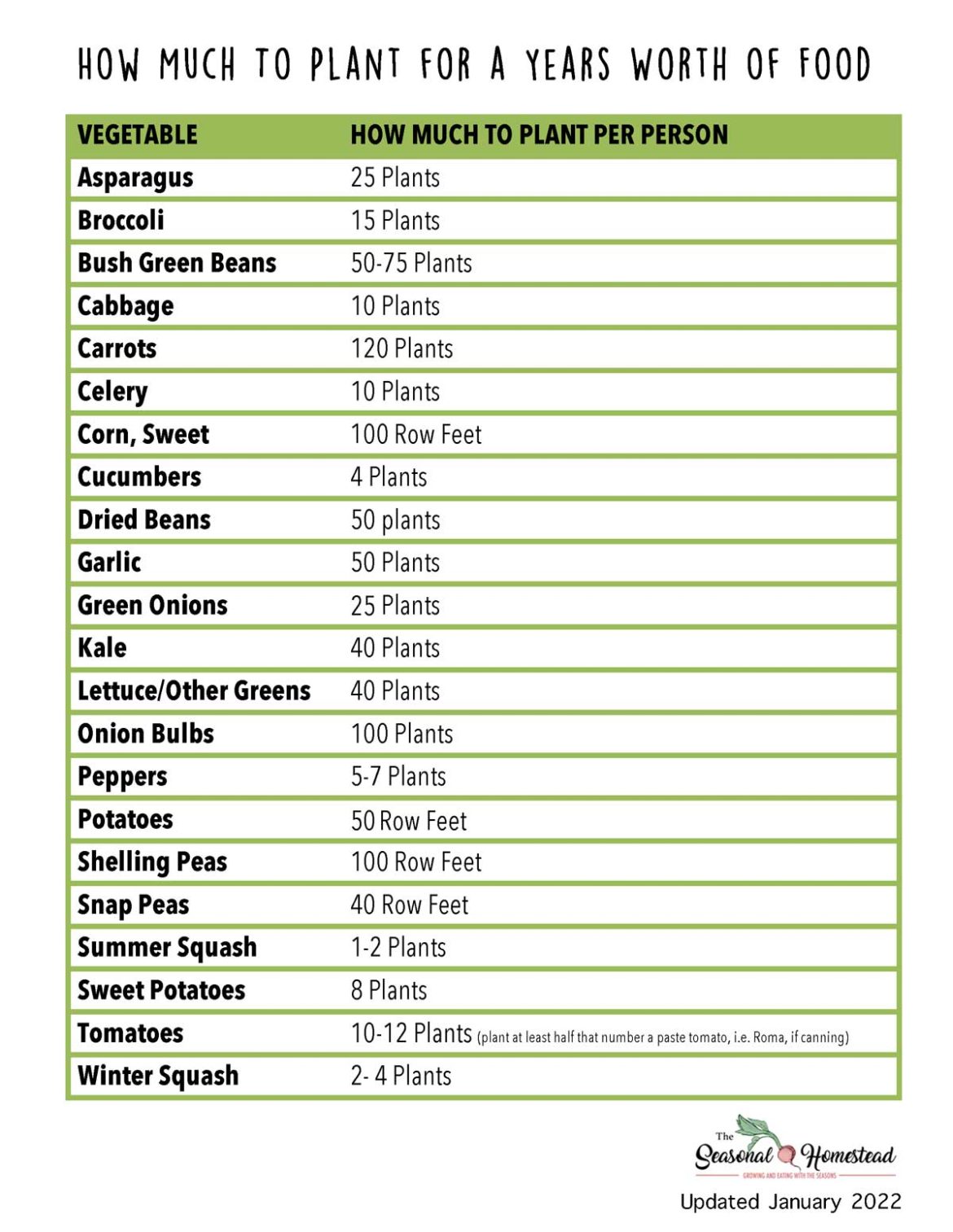

Joylynn Hardesty wrote:One of our Permie people made a staple crop calculator. I use it to plan my garden.

Thanks for the hat tip, Joylynn! And I'm glad you've been successfully using it to plan your garden!

I have some insights after the last few years of using my calculator and practically growing all of my own food.

For starters, the calculator is designed around relatively shelf-stable, high-calorie, staple foods. It will help you make sure you have enough calories, but it's nutrition agnostic. If you grow enough of these foods, you will have enough, and most of them will last in the pantry for years if you have excess. But they still need to be augmented with greens, fruit, nuts, and all the other vegetables that one wants to eat. Since these other things are way more variable in their production, and generally way lower in calories, I treat them as having 0 calories for the purposes of planning my garden. They aren't 0 calories, and the reality is that when tomatoes were at their peak, I was eating about 10% of my calories from tomatoes alone this season. Ditto with zucchini. Because I can set aside that 10% of calories from my staple crops for a year that I get a bad yield, I don't change my math based on what I hope to produce from those low-calorie crops (or from foraging, fishing, hunting, etc.) I treat it as a bonus that I can put in savings for a rainy day. Part of this is because the more perishable things are a coin flip. It doesn't matter if you can grow 25% of your calories from tomatoes if you get them all at once and don't have the time and energy to actually preserve them. Expect that you won't. If you do, that's a bonus.

As Abe said, start tracking now. You can't know how much you need if you don't know how much you're actually eating. I think it's important to eat the way you plan to eat if you were growing your own food and keep track of how much you're eating. Growing and eating everything from scratch is a lot of labor, and it's often very different food than we eat if we're buying our food. Make sure you're actually capable of eating the way you plan to eat before you invest a bunch of time, energy, and money into growing the food. If you grow a bunch of food that you won't eat, either because it's too much work, or because you don't like it, then that's a net loss on all counts. Of course, dietary patterns are learned, and taste preferences depend on our eating patterns. It takes 1-3 months for the palate to adapt to dietary changes, so if this is a way you want to eat, you very well might have to force yourself to eat this way for a few months before you actually enjoy it. Continuing to eat processed food while trying to make this transition just keeps your tongue wired for intense, manufactured flavors that keep you from appreciated the subtle nuances of more natural foods.

You also need to know that what you're eating is nutritionally complete. Love it or hate it, the commercial food system at least enriches foods to make up for the generally poor diets that people eat. If you switch to a natural diet and aren't actively pursuing variety in your diet, you will likely develop nutrient deficiencies. Something like 80% of Americans are low in vitamin B12 in spite of all of the enriched food. You won't know that you're not getting enough of a nutrient until it causes you problems... pain, fatigue, confusion, lack of balance, insomnia, mood swings, brain fog, psychosis, and eventually death. Not saying this to scare you, just to underline how important tracking is as you switch to growing your own. Getting some of these nutrients requires eating things that are bitter, or otherwise unpalatable to so many humans these days. Tracking with something like Cronometer is great for getting an in depth nutritional analysis of your diet and figuring out what adjustments you need to make.

I use the calculator both ways. Both to plan my garden, and at the end of the season, when I update it with the weights of things I was actually able to harvest. This year, it tells me that the staple crops I was able to harvest are roughly 50% of my total calories. 50% is still a lot, though not the 100% I would prefer. But I'm confident that I will make up for the rest with the fruit that I forage and the other vegetables that I harvest. Like the aforementioned tomatoes. There's no telling what will do well in any given season. Corn and squash are reliable here. Potatoes and amaranth can do well, but they haven't for me yet with my poor soil and lack of water. I will keep planting them, and expect yields to improve, but I can't count on them yet like I can corn and squash, so I don't plant them in excess. Updating the calculator at the end of the season lets me know which things are worth actually putting time and energy into, and which are just for fun and enjoyment.

For everything else, it's a matter of tracking how much you eat in a given week and planting accordingly. If you eat 10 carrots a week, plant 10 carrots a week (or enough so that you can have 10 carrots a week for as long as you can grow and store them.) That doesn't mean you only plant 10 seeds. You have to account for imperfect germination, pests, disease, thinning (which is incredibly important if you're also saving your own seeds... which you should at some point), etc. Expect things to fail. How much "extra" you plant is entirely down to how much space you have and how much you can risk not having enough of something. And you have to factor is seasonality. As you start eating the way you plan to grow, keep in mind when things are actually in season where you are. Don't buy things out of season and track them with the expectation that you'll be able to grow them out of season. Practically, you won't have fresh tomatoes in winter, so don't buy them in winter and expect that that's what your diet will be like when you're growing your own. Most areas, especially with a lot of u-pick or farmers markets, will have a calendar of what's in season when. Shop accordingly. It's also usually cheaper, since then it's not being shipped halfway across the world.

But the most important thing is to not expect to grow everything in your first year. You might be able to if you have enough resources, but there's a learning curve. And it's hard to know what will actually perform well at your site, and with the methods you're willing to employ, until you actually spend time putting seeds in the ground, seeing what happens, and adjusting accordingly. I expected potatoes and amaranth to be much bigger parts of my diet, but they just haven't performed well enough yet. Which is the other good reason to save seeds. Yields improve exponentially from one season to the next when you're saving seeds from your best plants, the plants that are already happy with your conditions. The weight of my corn nearly doubled this generation compared to last generation simply because I was saving seed from my best cobs.

Take it slow, be realistic, avoid the temptation to do too much (if you juggle too many plates, you just end up breaking all of them.) Better to figure these things out while you have the time and space to explore than when you're actually depending on that food like I was. Best of luck!

8

8

13

13

6

6

7

7

3

3

6

6

4

4

7

7

7

7

4

4