Justin Rhodes 45 minute video tour of wheaton labs basecamp

will be released to subscribers in:

soon!

Chris

1

1

A build too cool to miss:Mike's GreenhouseA great example:Joseph's Garden

All the soil info you'll ever need:

Redhawk's excellent soil-building series

1

1

List of Bryant RedHawk's Epic Soil Series Threads We love visitors, that's why we live in a secluded cabin deep in the woods. "Buzzard's Roost (Asnikiye Heca) Farm." Promoting permaculture to save our planet.

Travis Johnson wrote:

My own tests on making biochar with pine at significant scale (1 full cord) ended dismally. It either fully burned up to ash, or just scorched the blocks of wood, but did not produce biochar.

A build too cool to miss:Mike's GreenhouseA great example:Joseph's Garden

All the soil info you'll ever need:

Redhawk's excellent soil-building series

3

3

6

6

Trace Oswald wrote:

Application rates is still very much an ongoing topic. To complicate things further, I have seen growth tests that show some plants grow best at 10% biochar, some at 20%, some at 30%. The good news is, that unless you are making truly enormous amounts, I think not having enough is going to be a bigger concern than too much. For a starting point, I think I would try to get to 20%, and maybe test some areas with more.

Bryant RedHawk wrote:hau Chris, I do believe that the rates of decay you mentioned for pinus species was for intact trees, which would not particularly be the same for char made from those trees.

Bryant RedHawk wrote:

Now if you were doing the partial burn off, such as the way they make the charcoal for BBQ and Grilling, you don't have pyrolyzed wood, you have partially carbonized wood, because there are still many contaminates present, that weren't burnt off in the making of charcoal.

The differentiation is important since charcoal will deteriorate at a faster pace than pyrolyzed woods would, the contaminates are what cause the difference in decay rate.

...

I wouldn't worry so much about getting that pyrolyzing heat into the downed wood as much as I'd work to get it all partially burnt, then broken up into small chunks and spread over the soil (the smaller the chunks the better this works).

Once you have the char spread over the ground, you can inoculate with microorganisms with compost additions and or mushroom slurries.

Travis Johnson wrote:

My own tests on making biochar with pine at significant scale (1 full cord) ended dismally. It either fully burned up to ash, or just scorched the blocks of wood, but did not produce biochar.

Chris

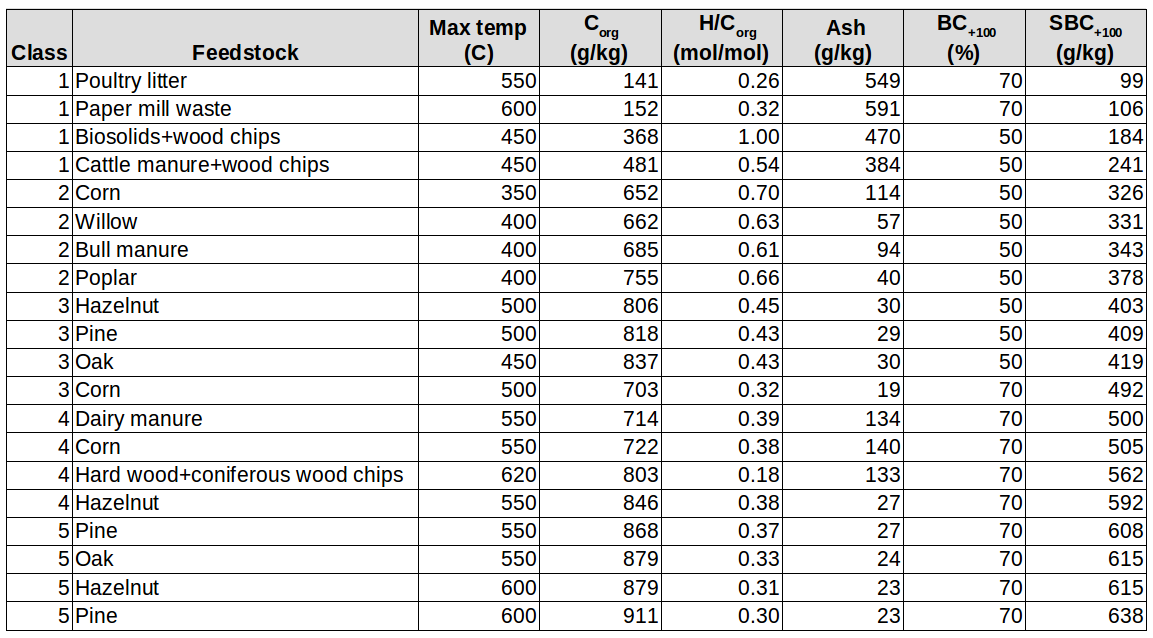

| Class | sBC+100 (g/kg) |

|---|---|

| 1 | < 300 |

| 2 | 300-400 |

| 3 | 400-500 |

| 4 | 500-600 |

| 5 | > 600 |

2

2

Moderator, Treatment Free Beekeepers group on Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/treatmentfreebeekeepers/

2

2

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

-Robert A. Heinlein

2

2

List of Bryant RedHawk's Epic Soil Series Threads We love visitors, that's why we live in a secluded cabin deep in the woods. "Buzzard's Roost (Asnikiye Heca) Farm." Promoting permaculture to save our planet.

2

2

My tree nursery: https://mountaintimefarm.com/

1

1

The holy trinity of wholesomeness: Fred Rogers - be kind to others; Steve Irwin - be kind to animals; Bob Ross - be kind to yourself

Mark Brunnr wrote:My own property is 99% pines right now, and my plan is to trim off the branches when I fell trees for a wofati, and that following winter burn the branches with the target of creating biochar for my first garden the following spring. I dropped a few very small pines (like 2-3" diameter, 15' tall) that were overcrowding a parent tree, and after 18 months most still have all their needles still, let alone any decay of the wood. So the biochar route seems like the way to go there. Next step is convincing the neighbors to let me haul away their slash piles instead of burning them!

1

1

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

-Robert A. Heinlein

| I agree. Here's the link: http://stoves2.com |