Fascinating topic.

Let's see if I can bring in a few themes that have not been covered yet:

Human Overpopulation - do we know what's causing it?

More specifically, if we are suggesting a change in family planning behavior as an appropriate response, do we know of any opposite change in behavior that helped to cause it in the first place?

Do we know of any stable, healthy, sustainable behavior patterns or family structures that are consistent with human nature, but don't cause population explosion?

1) Reducing Family Size:

Did it happen "because" people started having more than 2 kids each? Or did people back before overpopulation tend to have more than 2 kids per couple?

(I believe it's the latter, at least in the 20th century. How did we have huge families, yet avoid overpopulation earlier in history? Overpopulation can also be seen as "a shortage of dead people." It's not pleasant, but it is worth remembering that this is what our ancestors would have called "a good problem to have.")

2) Abstaining from Reproduction:

This seems like a totally acceptable personal choice.

My question would be is it necessary (or ethical) to impose it on other people, or even to make ethical judgements about other people's choices in this space?

A) Is it "normal" or natural for some individuals not to want to have kids? Most certainly.

A lot of species have "breeding pairs" and non-breeding relatives, like a wolf pack; or bachelors who don't breed in herds with a dominant male stud; or queens who do all the brood-laying while others mind the nursery and work the fields. I remember a lot of stories of sisters and brothers "keeping house" together into adulthood, sometimes staying together even if the brother married. There's a lot of evidence for single aunts and uncles as part of a successful clan.

Might it become more normal to not have kids, as we achieve larger colony sizes and urban densities?

Could be - a lot of people find creative cultural outlets and leave a 'legacy' other than their own genetic seed. But we have a weird thing where we use densely crowded settings for reproduction: festivals, cities, and other crowd scenes to be associated with young adults seeking mates. (Family groups often live further out, where it's easier to feed and shelter and protect a family group, and the only pheromones and germs are "family germs" and not-sexy pheromones.)

Modern societies do have honorable traditions around celibrate members - religious orders, career-climbers, aunts and uncles. We have also had dishonorable sterilization, like making eunuchs out of slaves, or sterilizing certain classes of criminal, retarded, "crazies," etc. We clearly consider it's possible to have a valuable life as a non-reproducing person. Even on pure economics, nobody would bother to castrate slaves unless they were somehow seen as more valuable (for specific purposes at least) after castration.

B) The reason I question the ethics of declaring abstention to be ethically good:

Kinda like polygamy could work in theory, but in our culture it tends to lead to a LOT of abuse of young women (and shunning of young men)...

I think that deciding for yourself not to have children is a perfectly ethical choice, but declaring that it is unethical to have children except in the "right" circumstances leads to a lot of abuse.

Bastards, children of single mothers, and now even children from prolific families may be subject to reflected stigmas by their parent's decision to flout social expectations.

Bastards were mean, stereotypically, because they were subject to abuse and had few legal rights.

Poor families with many kids are now seen as bringing poverty upon themselves, rather than being poor because there is not enough work to make a large, healthy, and tight-knit family an economic asset.

If the "right" circumstances are defined as economic/material, then you get situations where "poor people who should not have so many kids" are consistently imagined in popular culture as black or Latino (or religious minorities); it reinforces bigotry. And permies who live off-grid are committing child abuse by following their non-materialistic values.

If the "right" circumstances are seen as legal or religious marriage, then you can get abuses and coercion in all kinds of directions - teen pregnancy, bastardy, birth control, abortion, medical sterilization of "loose women" by religious hospitals when the medical complaint was a gall bladder infection just on the assumption that someone might get pregnant inappropriately - that permanent, involuntary sterility was "better" than a possible too-early pregnancy.

We might at some point evolve into a more connected, committed local culture, where social pressures to "do the right thing" helped reinforce the ethical choices that allow the whole group to remain healthier.

Where healthy, well-respected women bear the "right" number of babies, and somehow every neighboring group exhibits similar self-control.

But it seems much more likely that a culture that tells women when and how and who should/shouldn't have kids is displaying symptoms of being abusive, corrupt, controlling, and power-hungry. Women's bodies and lives are more directly affected by any "debate" about whether a particular child should be born. But everyone is affected when social pressures make it "wrong" to indulge our natural urges to connect with other human beings - through many degrees of affection, physical contact, sex, or raising a family together.

Basically - declaring a natural urge to be "wrong" doesn't make it go away. It just makes it more complicated, and harder for living, breathing, biological, human beings to navigate their lives and social identities.

The solution to a problem is rarely its exact opposite.

If excessive fecundity is seen as the problem, then abstention or sterilization is an obvious solution - but sterilization is not a sustainable choice for every human being, and therefore it fails that ethical test of "would it still be a virtue if everyone did it?"

In problems of excess, the obvious sustainable solutions are moderation, or creative re-direction.

We can fix some of the social problems that lead to excessive reproduction - women's education is often mentioned, opening more options for economic survival, identity, and creative satisfaction - and not denying motherhood, but postponing it a bit in ways that lead to smaller family sizes without coercion.

Less discussed is the equally-important work of developing a strong sense of masculine empowerment around being a loving, nurturing father/protector rather than a "tough," stud, or controlling authority figure. I'm extremely encouraged by the number of men I see doing these simple acts of nurturing, swapping days off work to be home with the kids, brilliant cooks, excellent daddy story-time. It works its way into literature, like Terry Pratchett's Sam Vimes character (a street-smart beat cop turned force of nature) beating the bad guys in time to go read bedtime stories with Young Sam.

I don't know if there are any statistics on how men's ability to change a diaper affects the birth rate, but it certainly affects the quality and possibilities of family life.

As with cars - if we could get all the people who hate their commute to stop doing it, we'd fix 80% of the problem while improving people's quality of life.

So with reproductive abstention: If we can make it easy and honorable for people who don't want kids to avoid them, and make sure there are alternatives that fill some of the cravings (for love, affection, security, status/respect, even physical rapport), then this choice becomes part of the solution without becoming a coercive nightmare. Making childlessness a genuine, humane alternative will require reaching out and helping each other to feel loved, supported, free to choose a satisfying life, and connected to the fate of humanity through a definition larger than the nuclear family.

You could make an argument that if you abstain from public sanitation infrastructure and from international commerce, that you are doing more to restore equilibrium than someone who abstains from having one child.

3) Reasoning/Thoughtful People:

Did overpopulation because we are irrational little biological bunnies, or because we began to use reason to ensure our own success at the expense of other species?

4) or did it have more to do with other factors?

What changed, that tipped the world from a stable state to overpopulation?

A.) Human Nature: in the form of tool use, social organization, creativity, and eventually agriculture and industry.

You could argue that "The 6th Extinction" has been going on since the end of the last Ice age, with tool-adept humans changing the conditions of "fitness" so that many other species were not longer able to maintain reproductive equilibrium. (In the book of that title, the author argues just that, and points particularly to the reproductive strategy of being a very large but slow-reproducing species, like elephants or wooly rhinos, which are not really subject to predation as adults. She found data to suggest that a human population that only occasionally hunted these animals - maybe once or twice a generation - could slowly tip them out of balance. Any successful predator is going to have similar impacts on species it preys on - like the North American cheetah did on pronghorn antelope's development, and presumably the extinction of any slower species of antelope. Whether Neanderthals, with a fixed tool set, would have a similar effect compared to Homo Sapiens, with our rapidly changing selections of tools and artifacts, is not proven - but I suppose it might be easier for the rest of Nature to reach equilibrium with any homonid, if we had more consistent and limited effects on it.)

B.) Human Reason: the current population growth curve gets really noticeable after the worst Black Plague in Europe - around the beginning of the Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment, AKA the Age of Reason. That's when we started convincing ourselves to implement measures like public sanitation, to allow doctors to actually study the human body instead of ancient medical Bibles/Classics in translation, and so on. It was a little later that we stopped burning witches, which deserves its own whole commentary on the relationship between reason, superstition, women's health, and social/patriarchal control. Witch-hunts and magic pills aside, I have seen convincing arguments that public sanitation is the #1 factor in the current population growth, even above antibiotics or any other medical advances; doctors only began to seriously compete with midwives for maternal survival rates after they started washing their hands.

Despite their rigid stance against contraception, simple historical correlations could suggest that the

Roman Catholic Church policies may have been better at preventing over-population than the subsequent Protestant capitalism, or secular rational eras. (I'm not saying it's true. It could equally be argued that the Church and State efforts to pronounce policy on private reproduction, and even our own discussion as if there was a policy to be determined, are all part of the same thing: an ongoing experiment in turning the world into people, since the dawn of agriculture, as in Daniel Quinn's

Ishmael.)

C.) Biological Population Curves and the Fossil Fuel Bloom:

As a dusting of iron over the sea brings forth an algae bloom, or a pile of juicy ripe fruit begets fermentation (a yeast bloom, with flocking piles of happy drunken fruit-eating animals): so does the introduction of highly concentrated energy sources produce a corresponding bloom in the population [of humans] able to consume them. This bloom of people is amoral: neither more or less ethical than a bloom of rabbits, algae, yeast, etc. However, if we don't want to suffer the same boom-and-bust consequences, then it's nice to imagine we could use reason to anticipate and alter the crash.

Are we superior to other creatures (the Church view), or are we just one more natural species subject to the same biological, natural laws?

Is there historical evidence that people are somehow better-able to resist crashes than other species? We are pretty good at finding our limiting resources as a social group, like water in the desert, for long enough to build up an army and force access to the needed resources. And we are uniquely good at creating 'domestic species,' there are just a few other known examples of species that do this.

But I don't know if that is evidence that we are capable of self-restraint at the level necessary to reduce the population in anticipation of a crisis. Whether we feel rational behavior to be superior, or part of the thinking that is causing the problem, the bottom line is that we do seem to be subject to the same observable biological laws as other species, certainly other social mammals, and we may find it easier to predict the outcomes than to control them.

D.) Global Climate Change: You could say that the end of the last Ice Ages was the cause of de-stabilizing Ice Age ecosystems, and that human beings were either put on the planet to accelerate this warming trend (if you believe "there's a purpose to everything") or that we are one of a number of species adapting as we can to the ever-changing environment. In other words, it was never stable to begin with, and the fact that the human-and-domestic system is thriving while remnants of Ice Age, Cretaceous, etc. are waning is just evolution doing its thing during a big change of global climate.

E.) Consumer Culture: If you agree that not just the population, but the per-capita resource consumption is a big part of why this particular population bloom is so dramatic, then getting our lifestyles down to something like Cuban standards is an ethical answer. We don't need to give up houses, but it would not hurt to share them (and the washer-dryer) with a few more of our favorite people. In large part, this entire line of thought would require caring more about people and other living beings than about "stuff". To continue my example - can you culturally and personally make it easy for someone to share a washing machine, and commit to getting it repaired together if something goes wrong, rather than avoiding sharing because it might break, or someone might get upset, or a renter might not know what a lint trap is? I'm still thinking about buying a washing machine of my own, because there are issues with the different ones that I currently share: cost and distance to the laundromat, small capacity and extra-cautious ownership for my in-laws that are closest, and seasonally limited water on my friends' farm.

It is arguably true that a child will arithmetically increase resource consumption, if you assume they consume similar to the parent.

But I think there's also an argument to be made that someone who owns less than 1 car per person, having a child they raise with similar resourcefulness, may have less impact in aggregate (both parents and child) than someone who has no children but 3 cars. Or takes a lot of "service vacations." Or buys stock in X corp, and so on.

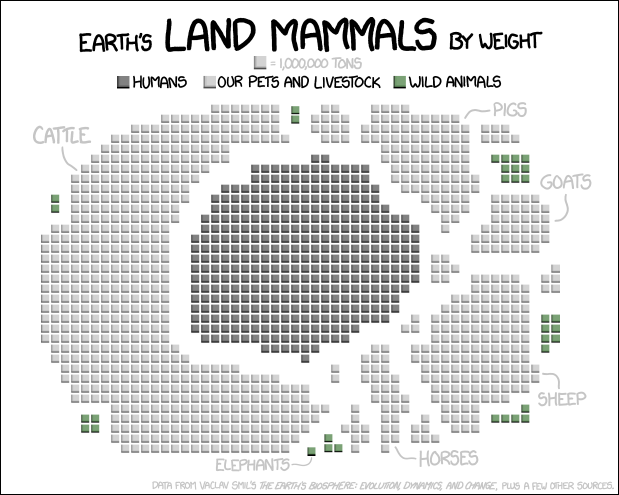

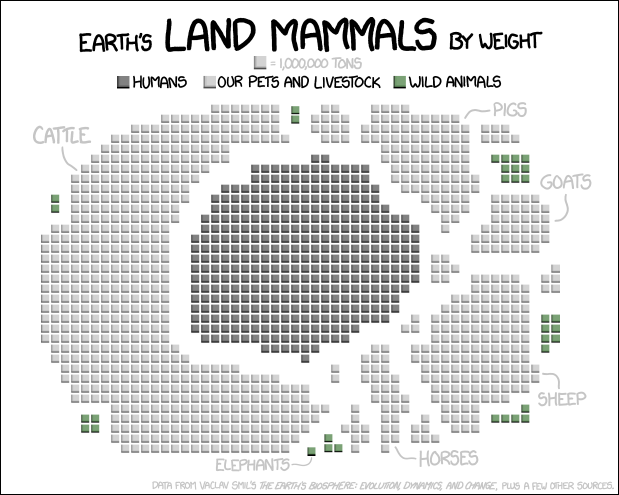

Regardless, the result looks like this:

https://xkcd.com/1338/

Undeniably, we have a lot more human beings and domestic animals than the Earth did when we first evolved on it. And there are a lot of reasons to think this population density is not sustainable, and that we may be witnessing the tipping point where life "after" will not look very much like "before." Whether "after" might involve a smaller and wiser human population making do with a smaller but abundant garden, or some kind of massive depletion of life on earth that wipes out all species larger than rats, is hard to predict, as we don't have a lot of (or any) other examples of this

type of extinction at the global scale.

Scientific Basis for Population Ethics:

Given the difficulty of predicting, and the number of other impacts that can be altered with small but widespread lifestyle changes, it seems cruel to condemn someone's family choices on the basis of over-population.

Rationally, if a mass-murderer's actions or biodegradable chemical weapons (WMD) can be seen as helping the situation, then ethics as we know them are out the window. It's pretty hard to define "decent" or "ethical" choices here.

I would much rather live around a family raising 6 happy children, than a mass murderer, myself.

"The Ends Justify the Means" is a pretty widely reviled, non-valid ethical argument. Especially when we cannot fully predict or control the ends.

If you want to stick with core ethics of caring/doing no harm, and fairness, yet apply that scientifically beyond the current human population to all life on Earth, then we need to fit our actions somewhere in the thick part of a bell curve that allows for a life-sustaining outcome.

No individual should be compelled personally to fix the problem to a greater degree than their personal responsibility for it.

An average of 1 or 2 kids per couple, with outliers from -1 to 5 (-1 being maternal and infant mortality in the first birth, or other situations involving a reduction in a genetic line), is pretty well forgivable as "replacement value or a little less."

I have a soft spot for larger families because I've seen so many that were really doing well, and raising kids with a strong sense of responsibility.

In a sense, a large family eating out of its own garden may be the opposite of the "Idiocracy" film's argument - there are thoughtful people who love kids, and have a lot of them for that reason, who raise some really spectacular kids.

In the event of a population crash, the survival traits that do come through may matter more than the painstakingly-leveled-off numbers before the crash. We could spend a long time arguing about what type of population reduction, evolutionarily speaking, would most likely result in a more stable, less overgrowth-prone human population. But aside from physical limits (like being on a small island), I have not seen a lot of evidence from other species of boom-and-crash population dynamics spontaneously stabilizing after a crash. It would be pretty amazing if we can pull it off.

So that's the theoretical. Boils down to "it's complicated."

By analogy, it's like farmers and sea fishermen and tribes and utility companies and cities and all pointing at each other and saying "You are killing the salmon!" when clearly, all of the above are contributing. Dams kill more salmon and prevent more reproduction than local fishing; the fish were clearly doing fine when it was just the tribes fishing them, but does that mean the tribes are exempt from changing their behavior when the situation changes?

(Not that they are necessarily unresponsive. But under treaty rights, you could argue that we as a society have massively violated our treaty agreements that the tribes could fish and hunt the ceded lands "in perpetuity." That clause, and our Western cultural expansion's sense of greed and entitlement, may be part of why the fish and the buffalo have been so mercilessly slaughtered - because the settlers saw them as belonging to someone else, a despised "other race", and while extinction was still controversial at the time, I don't think anybody doubted that reducing the wild game population would hurt the Indians more than the Settlers.)

Taking the theoretical down to the individual:

I don't think it's right, fair, correct, or productive, to put all the weight of this issue on the person deciding whether to have children. The "Idiocracy" argument about thoughtful people self-limiting while others don't doesn't entirely hold - because human society is about a lot more than just sex. Thoughtful people also don't poo in the well, or make war because of an ambiguous insult, or wind up living in a cardboard box because of thoughtless errors on the job; the detectable progression of our society toward over-thinking could be a strong argument that thoughtfulness does equate with reproductive success over certain time spans. (Ernie talks about "we've basically been breeding for autism;" specialization, maths/logic, and other aspects of the "spectrum" are definitely correlated with success in the modern world.)

However, much as I like intellectual discussions, I don't think thoughtfulness or reason are the defining arbiters of human worth. They seem almost more like birdsong - an attractive thing that we do amongst ourselves, but which means more in our own cultural context than to any outside species hearing the results.

Three arguments:

1) Historic: The age of Reason correlates with an extension of human average lifespan, and with a general lessening of atrocities and the crime rate. But it seems to achieve this by an axiom that is self-defeating: that humans can secure their well-being as a larger group by cooperating to exploit other species and "resources." Reasoning cultures have arguably improved our individual condition, but worsened the state of the larger world. If you believe some of the primitive skills/anthropologists, there's an argument to be made that the divide-and-conquer flavor of reason has resulted in worse conditions for much of humanity, as our population continues to outstrip our resources.

2) Psychological/Cultural: The cultures that seem to be most capable of living harmoniously and self-limiting seem to display a combination of highly-developed reasoning with an even more highly developed intuition and compassion. The culture must work with human nature, including the intense emotional needs and social needs of people, in order to produce a sustainable, healthy, balanced, and unselfish adult population.

Limiting our permitted behavior to the "rational," according to a lot of psychologists, can unintentially suppress deep needs and contribute to self-deception, addiction, denial, and projection.

A "rational" argument is often a lot less effective in changing people's behavior (even to ourselves) than compassion, empathy, humor, patience, understanding, healing, and the emotional development of a sense of mutual interest. In other words, it's irrational to look at human politics and history and then expect the population to respond to "rational" arguments rather than emotional or culturally-resonant appeals. If you could change people into rational beings, and then explain to them how my opinion is rational, then it would work so much better! But there is an endless trail of failed religions, failed governments, failed communities, and failed personal relationships that were all developed on the basis "If only people could be made different and better than we actually are, then we could...."

3) Human Nature/Personal: Science seems to demonstrate, ironically, that we are less rational than we think we are. There is some good research that suggests our bodies begin moving toward a decision measurable time increments before our rational mind comes up with its "decision" or reasoning - that we are in fact more like physical and emotional creatures who rationalize, rather than rational creatures who 'degrade' ourselves with the occasional emotional self-indulgence.

This seems supported by my observations of my own behavior, and particularly by watching my engineer father. He (like his brothers) is a genuinely caring, nice man, dedicated to his family, with the common flaw that engineers and designers have of wanting to rationally "reinvent" or "improve" something based on logic. For a trivial example, he believed firmly in the idea of sorting the silverware as it went into the dishwasher, to make it faster to unload. (My objections were: 1) sorting takes no more time before than after the wash, so there is no actual overall time savings just micro-management of other people's choices; and 2) putting spoons together results in rice and other foods sticking between the spoons during the wash cycle, and getting baked on during the drying cycle, so the dishes actually get harder to clean instead of being washed. To my mind, the axiomatic purpose of a dishwasher is not to save time, but to WASH THE DISHES, and the first goal must be met before the secondary goal of time-savings becomes relevant.)

But what it really came down to is probably that washing dishes was on the kids' chore chart, while emptying the dishwasher is the sort of thing that falls to a responsible parent to make sure is done BEFORE the meal prep, so that the kitchen stays usable. Teaching kids to seamlessly unload a dishwasher as soon as it done seems to fall into the realm of "if only people were somehow better than they are," also known as Magical Parenting.

For a deeper example, witness the amount of "work" that was done on Grandma's house after she died, before finally putting it on the market. A number of "home improvements" were undertaken, at some expense, until the house no longer looked or felt as much like Grandma's house. (Some of the improvements, like new rubber baseboard badly installed, didn't necessarily improve things so much as just make them different.) While sorting through her possessions, at one point, all 4 of her children and 2 beloved in-laws each individually re-organized a collection of tools for distribution to the grandkids. Each person had a "reason" for re-sorting the tools (by type, by cash value, into kits useful for specific activities, into mixed sets of roughly equal broad usefulness... at one point, someone had to be talked out of splitting up the silverware set and giving everyone 2 knives for "fairness"). To someone paying attention to the social and emotional atmosphere, it becomes obvious that this is an instinctive, near-ritualistic desire to touch Grandma and Grandpa now that they are gone, not a productive contribution. But it was productive on the deeper emotional level - saying goodbye mattered more than speed or fairness. Despite all this sorting, there were no arguments against making sewing kits for the girl grandchildren, and tool kits for the boys. Just as there was some discussion of keeping the house in the family, but ultimately no question that the fairest way to deal with the legacy was to sell it so it could be divided - material culture says it is not shared if one person's kids live in it for free, or it stands empty against the occasional visits of one couple, when it could be sold and turned into money to share out mathematically.

It was a fumbling, loving, imperfect attempt by grieving family to re-organize themselves, and remain together as a clan, after a deeply felt loss. The material and "rational" stood as proxy afor something more important.

So watch out for "rational" arguments around deeply emotional issues. Our society has given up a lot of its "superstitious" rituals around grief, loss, and mutual support; what is left are a lot of people with unhealed griefs and wounds, and a cultural context in which your voice will be respected more if you can make it a "rational" issue rather than being "irrational" about it. Rational literally means ratio, fraction - it is the process of cutting things up into little parts and proportions, examining them a step at a time. Rational thought can give us a lot of insight, but one thing it has never been able to do is make us whole.

Having children, for many people, is connected profoundly to deep issues about "being whole." Either in social standing, or in receiving and giving love, or in correcting an injustice (whether from one's own childhood, or the foster system, or jealousy of other siblings). Some of these things can be substituted. If presenting your mother with your college diploma or publishing a book will give you the same visceral satisfaction as presenting Grandma with a baby, then by all means, dedicate the book to her instead! Children don't need to be their parents' vicarious success.

But for some people, raising children is a vocation as strong as any career could ever be. For the most part, these are exactly the people who should be raising our children. Recognizing them depends on trusting their internal intuition, as well as external indicators of integrity like pursuing relevant qualifications or showing respect and helpfulness to other child-rearing families. It may not be 'rational' for a person to do this, any more than it's 'rational' to become a monk, or to take up the life of an Indian ascetic - it involves personal sacrifice and must be intrinsically the right thing for that person to do.

It could be counter-productive to talk someone out of having kids by breaking down their irrational choices into little pieces - if they are doing it for the wrong reasons, this can worsen the hurt that drives them. (Even mockery can be more effective than lecturing, when it comes to affecting someone else's behavior - but I would advocate compassion, trying to find out their reasons, their hesitations, and inquire whether they've considered an alternative that would seem to satisfy those same reasons.)

And if they are called to raise children in a spirit of wholeness and service, talking them into some other and less-fitting pursuit may eventually cause the same hurt, and drive them into materialistic substitutes.

We are socially very prone already to consider materialistic success as a substitute for wholeness; which, of course, leads to over-consumption, disconnect, reliance on trade infrastructure for daily survival, and strong emotional backlash on issues like over-population, over-consumption, global climate and resource crises (the climate is just one factor, we also have water, oil, soil loss, and salinity to worry about).

4) Well-being of Children, Values of Society:

There are also human development factors in how kids are raised. Based on personal experience and the corroborating theory of birth-order roles, I think the "oldest sibling" in a lot of households ends up extra-responsible, compared with only children or younger siblings, because they are often required to be helpful at an earlier age. This does not mean that I favor primogeniture - where only oldest siblings inherit - because the second sibling often ends up very competent too from pushing themselves to keep up with the first. Middle siblings may have more flexibility in their self-definition than oldest, youngest, or only children. It might be healthier for the children for some families to raise a big pack, while others go without, instead of spreading them out "fairly" at one or two children per couple.

Material wealth doesn't seem like a necessary prerequisite for raising responsible children. I'd say a minimum where you are not excessively deprived, like the threshold where money correlates with happiness, would be the only rational target - this seems to be a figure between $13,000 and $20,000/year. If you don't have enough to create physical security from starvation or losing your shelter, it affects happiness and stress. More than that does not correlate with happiness, nor physical well-being. But this income level, while it supports a childless couple quite happily, will not necessarily secure the approval of the state foster-care system unless you already own a home. A society that connects material wealth with well-being will want more wealth per child as "birthright," where a society that sees virtue in non-material or unselfish behavior might quite easily see a child's life as worthwhile if all they did was to help take care of their younger siblings in a refugee camp, for example.

5) Denial of Mortality:

Part of the emotional weight of this issue is that there is actually only one way to reduce the population: People die. Technically, the death rate has to exceed the birth rate. It is very hard to feel comfortable arguing that a lot of people should die sooner - it goes against all our social codes, unless we can somehow define these people-who-need-to-die as "other" or "not

real people." That's more or less what we've done with other species, and what we've largely stopped doing with other races in liberal society (well, are attempting to stop doing - we still seem comfortable defining "people-who-need-to-be-locked-up").

The few cases where that rational argument has been made in the 20th century to exterminate some group are almost universally reviled, and evidence from elephant cullings suggests that killing off a whole herd is actually healthier and less cruel than a "fair" culling of a few animals from many herds. (Traumatized elephant herds do not do as well as intact ones.) By that argument, a few large families and a lot of dead people could lead to a healthier human population than massive austerity measures like the Chinese "one-child" policy.

But we also know, at a deep level, that mortality is scary. Ernie points out that if the death rate exceeds the population's ability to bury their dead, tend to the abandoned domestic animals, and so on, you get a cloud of corruption and disease for something like 50 miles around the affected cities. The idea that we'd be back to a relatively stable situation if 6+ billion people dropped dead is terrifying, and it's unlikely that we could pull off such a drastic reduction without enormous impacts on other species as well.

All the weight of our terror and denial of mortality, all the traumatic aversion to war and catastrophy, pushes against even considering an increase in the death rate as a population solution.

A few courageous elders abstain from certain kinds of medical treatment, which is incredibly hard to watch - almost intolerable - if you love them and want to keep them around.

So it's easy to drop the weight of a whole lot of unexamined fear-of-death, alongside our guilt about overpopulation, on those people considering whether to have [more] children.

6) Psychological shadow-projection: Whether to have kids is deeply tied up with questions of personal and spiritual mortality.

It is equally rational to argue that someone should die, as that someone should not have a child. It may even be equally ethical, if your ethics is based on population dynamics and all species, rather than on a special weighting of the rights of innocents, or the sanctity of human life.

Pro-life (anti-abortion) folks, for the most part, have little problem with civilian casualties in war - protecting the children is an emotional issue, and so is supporting the warrior's freedom and the "freedoms" for which he fights.

But it's much easier to argue that someone ELSE should die, or someone ELSE should not have children, rather than point that finger back at oneself. That suggests a projection of responsibility, at least; we may be projecting other, unexamined fears and values along with it.

It is emotionally INTENSELY difficult to find a peaceful place from which to contemplate volunteering to die "early," watching your loved ones die "early," condemning unloved strangers to an early death because they won't be missed, or to never have children (despite wanting to do so) merely in order to leave a little more world for someone or something else that went ahead and indulged their procreative urges.

We have to grow up a LOT to see ourselves as part of a larger universe, to continue to make a stand for hope and justice, yet still feel like we've made our peace with our elders and the unborn so much that we can let them go.

Then the practical, intimate, and deeply personal:

Ernie and I wanted, and still want, to have children.

We will be lucky at this point to have the option.

We chose to wait until we knew how things would be with his injury, until we could afford health insurance for childbirth, until we had our feet under us.

However, it turns out that chronic pain and permanent injuries makes it increasingly difficult to physically produce children, as well as literally and figuratively difficult to get our feet under us.

We may never have the "perfect," responsible opportunity to bring a child into the world together. I doubt anybody does; there are pros and cons to every scenario in which to raise a family.

And we are at the stage of life where the likelihood of having children is diminishing with each passing year.

I have been grieving a lot lately over this.

It's doubtless partly biological, but not "just" a biological urge.

As a biological being, one could argue that all urges felt by carbon-based life forms are biological (including the urge to suppress urges with rational analysis - mistrust of biological urges may be biologically based in chemical influences, or childhood trauma reactions that are Pavlovian in their predictability).

As with all biological urges, there's a rational argument available for doing what I want:

My genetic line is well-represented - the extended family includes over 40 people at Thanksgiving, and my sisters and brother have produced 4 nieces and 2 nephews between them.

Ernie's line is not - he has one biological niece, and no prior children.

Ernie's line represents some unusually fine material, in my purely rational opinion.

I would argue that Ernie is a marine mammal, probably an Arctic marine mammal. (Scotch-Irish-and-Swede, but people say he looks Norwegian.) I don't know if these "sea-bears" are endangered, but there seem to be less of them now than there once were.

They have been sailors for many generations, meaning they are highly technically competent, large, physically very strong, with robust immune systems, and a whole snowball of cultural heritage and skills that lead to tremendous physical insights about observing the weather, water conditions, maritime ecology and biology, maintaining the various onboard life-support systems and by extension the infrastructure of civilization or homestead life, etc.

As commercial fishermen who worked small boats in familiar waters, they are arguably some of the last Western hunter-gatherers - they know their world in a way that is rare, and seems precious to me. Both Ernie and his father have been actively involved in salmon restoration, fisheries improvement, and both prefer to work line or pot fisheries (where you are limited to a relative percentage of the fish, which self-select for the most gullible; and a conscientious fisherman is able to return bycatch to the ocean still alive), rather than net or dredge "fishing" (AKA mining or strip-mining the sea).

The whole idea of raising people to be super-aware hunters, interdependent with their environment, is unfashionable in modern politics - it's better to be a San Francisco vegan, and sell the fishing rights to Chinese factory trawlers, right? But I think our dis-connect from the natural world is only possible in the temporary context of fossil fuels, and is part of the cultural value set that is driving us onward toward worsening the extinction point.

I think if we want to return to a human place in the spread of life on earth, we need more hook-and-line fishermen and fewer feed lots.

I would deeply love to help Ernie raise a child of his genetic line, in conditions condusive to passing on the whole package of genetic, epi-genetic, and cultural heritage.

I don't actually care as much about getting Ernie back out on boats, as I do about helping him raise future sailors, one way or another.

I think the human beings who survive the next few decades are going to need low-carbon sail transportation, and I think it will be a lot stronger if it has some working sailors actively developing the new version, instead of just recreational and academic perspectives.

We do have the option of training other people's kids, and we enjoy doing this and will continue to do it.

But there is a BIG difference in being thrown in a fish-hold as a playpen at age 3, by someone who was raised on boats by someone who was raised on boats back to Noah's grandbabies, and coming in as a school-raised 20-something. I've seen Ernie struggle even to develop workable instructions for someone substantially smaller than himself, because he's never had to do things in the way that a smaller person would do them. I also, half-joking, tell Ernie that we need at least 1 child as big as him, just to help me manage him when he gets senile. Most rest homes don't supply 6'6" nursing staff.

Could we raise someone else's kid in this way?

The foster care system does not allow our woodworker friend to let his foster son handle power tools until he turns 18. (Ernie could have the kid sailing in his own DIY boat without ever going beyond hand tools, but it's just one example of the vastly different expectations about what constitutes a "good" upbringing.) The system also puts limits on out-of-state travel, and international borders are tricky with a complex guardianship arrangement.

It seems very unlikely to raise a foster kid or adopted child, even if they are brought in very young, in the full family tradition of the Wisners.

We could more easily raise a sailor a day's journey from the sea, than we can imagine raising someone to this same level of competence by starting when they are 15 years too old for the most rapid learning. We can and do invite the nieces, nephews, and friends' children out on boat excursions, help others learn to build and maintain and operate boats, teach water-tracking, etc. But it's not the same as raising a kid together from the ground up, or even anywhere close to the ground.

Sometimes I imagine we might somehow inherit another sailor's kid, by some private arrangement where the state does not limit our ability to raise him or her in the maritime heritage. (Yes, "her" - Ernie's family line includes many female seacaptains going back to the Age of Sail, as well as women who raised the kids and gardened and ran small businesses while the sailors were gone.) "Rationally" considering ethical options to find a child from similar genetic stock, privately without the state's oversight, I have even considered advertising during/after the Rose Festival, as surrogate parents or co-parents for someone's accidental sailor-baby.

Oddly, I'm less comfortable with the idea of getting genetic material from a sperm bank, or going out carousing with sailors in hopes of bringing home a baby before I get too old. They are technically feasible, but it doesn't seem like the right choice for our lives right now. The second option feels like a betrayal of my marriage, and perhaps irresponsible - putting my 'wants' above my word.

And if we can't qualify for state-approved adoption due to "primitive" facilities, is it responsible (and would it be medically and legally supported) to enlist expensive technical assistance to produce a child just because it's biologically now/soon or never?

There is something ethically "safe" about adopting someone else's already-living child, especially if it's an orphan or helping-the-family situation. Nobody can argue with that as a "good thing to do," because while bringing an extra child into the world might be irresponsible, making an existing child's life better instead of horrible is axiomatically good. (I think it's actually good too - I still believe that well-balanced human beings who feel secure and loved are likely to have better effects on the planet than lonely and deprived ones.)

Going to a lot of technical trouble and expense to produce an extra child, despite a situation that is not biologically or financially "optimal," (and especially to selfishly request a specific genetic 'spec') seems more self-indulgent than practical. It's not legal to offer a stranger at the Rose Festival a few grand to not abort their impending child, but you can pay something like $30,000 to a fertility clinic, or I'm-not-sure-what for adoption.

I think the most defensible, and the most comfortable, approach is to keep trying as we can. To put together a legal residence with a legal second bedroom. To do our best to earn enough money and keep up the insurance payments for medical support. "If everything was better," then we could consider medical fertility options. I was hoping to do this before age 35, now age 40 seems like it's closing in fast. But it could be possible in the early 40s too.

Money, despite being an imaginary social convention, would certainly increase our range of options, and improving quality of life is a good motivator to commit to making some real money in the next little while.

I do wonder if biology has a point here.

Currently, biology is "winning" by making us not have children despite our best efforts.

If we are not physically in condition to make babies, then it would follow that we would have some physically bad days in the process of raising kids.

Our everyday life is not exactly easy, and we debated whether it was responsible even to keep a stray dog last year. (We did, and it's working out great so far.)

It's not even a moot point - "moot" being a discussion in council - because discussion and reasoning don't ultimately solve the fundamental biological problem.

Rationally - I've seen kids turn out amazingly whose parents were physically impaired, or even emotionally traumatized to the point where they were not able to be consistent caregivers. If the goal is to step down the population while increasing the social responsibility factor, only children who have helped look out for their parents from an early age seem to be an asset to the cause. They can be as responsible as oldest-siblings, and have similar freedom of self-expression as middle siblings. Of course, impaired parents can also produce some spectacular juvenile delinquents. Getting and accepting support from beyond the nuclear family makes a difference here.

Ernie has considered having his injured leg amputated - but it is not considered medically advisable, nor can they guarantee any respite from the pain (it might become "phantom pain" of similar intensity). He might end up in similar pain, far less mobile, and incredibly depressed. Or he might end up starting a second life as an only-slightly-weather-sensitive, one-legged sailor, with less pain and more option to actively participate in all sorts of activities, including starting a family.

I think that's what hurts the most in considering whether we can do anything about the situation. Because it all comes back to the fact that my partner is in incredible, for anyone else intolerable, pain.

You don't really have a choice whether to tolerate it - you have a choice whether to live with it, or stop living and start trying to die to get away from it.

(I think that's a metaphor for this whole decision, really - do you embrace the painful hope of being part of an uncertain future, or not?

Do you suppose rhinos or deer wonder, "What's the point of bringing a new faun into all this?")

Despite the pain, Ernie is great with other people's kids, and with the dogs, and I believe it's rational to suppose we could do a damned fine job raising another sailor or two. Or an accountant, if the ironic law of parenting has its way.

Certainly we have more training and experience than a lot of parents, and we have a lot of hope and love to offer, along with the strong dose of realism that is part of our approach to living responsibly and caring for the future of life on Earth.

Like Tyler, I do have a sense of the "missed" children. The fact that a child is hypothetical does not stop you from missing it, though I'm sure it's different from grieving a miscarriage or lost child.

I remember specifically a moment when I started to feel a longing to meet them, and looking forward to it - and another moment when I felt that they might not be able to come through me after all. Didn't get as far as names - just a sense of the soul, or personality. I believe they would be about 8 to 12 years old right now, somewhere, if those intuitions were accurate. I sometimes wonder if I will "meet them" anyway - find a soul or two like that who become sort of surrogate children, at some point.

I feel we need to balance the health, psychology, and well-being of the children who we do raise against the ethics of self-restraint. "Later, longer, fewer" is a socially acceptable method for reducing child birth rates, which trades on our love of personal freedom and procrastination - but it may not produce the best (healthiest) results for individuals.

Knowing what I do now about reproductive health, I recognize that life can take away the option.

The child and mother are somewhat more likely to be healthy with a late-teen to early-thirties childbearing age, and it can become more difficult for men to father children with increasing age or injury.

I would encourage anyone who is young and healthy and wants children, or even those families where there's a devastating injury to deal with but you still want children "eventually," to go ahead sooner rather than later. Not everyone wants to raise children, and there are plenty of people who won't (either by choice, or by accident).

If you enjoyed carrying your first child, and want to do it again - that seems like an important capacity to keep in the human species! Maternal mortality due to our big heads and small upright-walking pelvis is a huge liability for our species, and I think successful natural childbirth is a pretty big indicator that you have some good genetic material to pass on. (I would say the same thing about genetic lines with strong backs and long-lasting knees, but they're harder to select for in youth.)

You will never be in the "perfect" position to start your family. It is not physically possible to have the perfect average of 1.5 or 2.2 or whatever number of "average" children turns out to be fair for some arbitrary population target. Some people will have more, and some less, if that average is to be achieved. Have the one(s) you want, and make sure they know they are loved, and see how it goes. If the number is smaller than 4, then the most important issue is probably not the overpopulation target - it's going to be something in your life that is pulling toward one choice or the other as the right one for your family.

The necessary experience to help raise a child successfully in this younger age range can and should be supplemented with help from older members of the family and community - make sure you stay in touch with people who will help raise your child, even if they don't share 100% of your value set. People who share only a small part of your conscious value set can still teach your kids incredible life lessons.

Grandparents often get the first option - another reason to go ahead while the potential grandparents are still relatively young, as well.

I've seen some very successful multi-generation co-care arrangements that allow all 4 parents and grandparents to maintain a satisfying career, and social life, while raising some healthy and well-adjusted kids. (Working 4 10's in rotation, with each parent taking a different day with the kids, is often part of the arrangement. My sister still has a very close relationship with some cousins she helped nanny, working 2 days a week in the office and 3 with the kids, while each parent worked 4 days in the office and 1 off, plus weekends, with the kids.)

What I'm really hoping for right now is that my sadness over not having my own kids (yet) won't stop me from being involved and supportive other people's kids.

It's interesting - hanging out with any given individual child seems to go great, but I'm prone to fits of self-pity thinking about the general topic of "babies."

I think about being more involved with my nieces and nephews in compensation, but don't do much about it (we live too far away for convenient routine visits, though I could do more birthday-packages and storytime-calls).

Of course, thinking about nieces and nephews as a "condolence prize" is more likely to create a slight aversion (connecting the thought of them with this sadness); it's more motivating to think of them individually, or to find flattering things that we have in common as points of connection. (Like my oldest niece's long memory for our "edible flower" adventures on an early visit.)

A lot of my energy right now is going into the other end: helping to care for adult friends and family, rather than cultivating relationships with younger people.

So there's even a big question hanging over the whole topic:

Am I sad about this topic because of the fading chance to have kids of my own?

Or because my drive to have kids is actively conflicting with other drives, like selfishness, or caring for Ernie and his folks, or the perceived dilemma between making a "big" public contribution and being a "big" part of private/family life?

Or is having babies a metaphor for something else entirely, that's a sore point right now?

It's all too easy to keep on going with a fixed set of complaints and prejudices, and being sad about this is becoming a habit.

I wonder if there's some subconscious insight, just waiting to pop out and take this whole emotional arc in a new direction.

My take right now at age 39:

Have a kid, or a few, if you want. Share them.

If you don't want to have [more] kids, enjoy your freedom, and connect with people in other ways.

If you are not sure, wait a few years, but don't wait forever.

And stay off other people's backs about their family size or choices (what's best for a child, and best for the world, is not nearly as obvious as we'd like to think).

-Erica

3

3

2

2

.

.

1

1

1

1

3

3

2

2

1

1

2

2

2

2

1

1

) that they will build on what I have created. I actually don't worry about it much. I bet those folks will be nice.

) that they will build on what I have created. I actually don't worry about it much. I bet those folks will be nice.  I hope I get get to meet some of them, but I don't expect to.

I hope I get get to meet some of them, but I don't expect to.

1

1

7

7

1

1

2

2

4

4

3

3

1

1

1

1

1

1

4

4

2

2

1

1

1

1

4

4

1

1

1

1

5

5

, I think you are probably a part of the population that understands more than the majority too, but that we both have a different way in front of us to see that end. In the case of one not having children, they have work to do bringing people from other places. Building a permaculture population by depleting the zoo population is a fine thing to do. Be forewarned that it will take more time in the zoo and less time learning to live outside of the zoo. (In the wild?)

, I think you are probably a part of the population that understands more than the majority too, but that we both have a different way in front of us to see that end. In the case of one not having children, they have work to do bringing people from other places. Building a permaculture population by depleting the zoo population is a fine thing to do. Be forewarned that it will take more time in the zoo and less time learning to live outside of the zoo. (In the wild?)

everything is subject to change.

everything is subject to change.

9

9

1

1

1

1