Glenn Herbert wrote:I think you have been misled by a lot of youtube videos, which are not made by people who build rocket mass heaters regularly, but by experimenters who are familiar with woodstoves and maybe rocket cooking stoves.

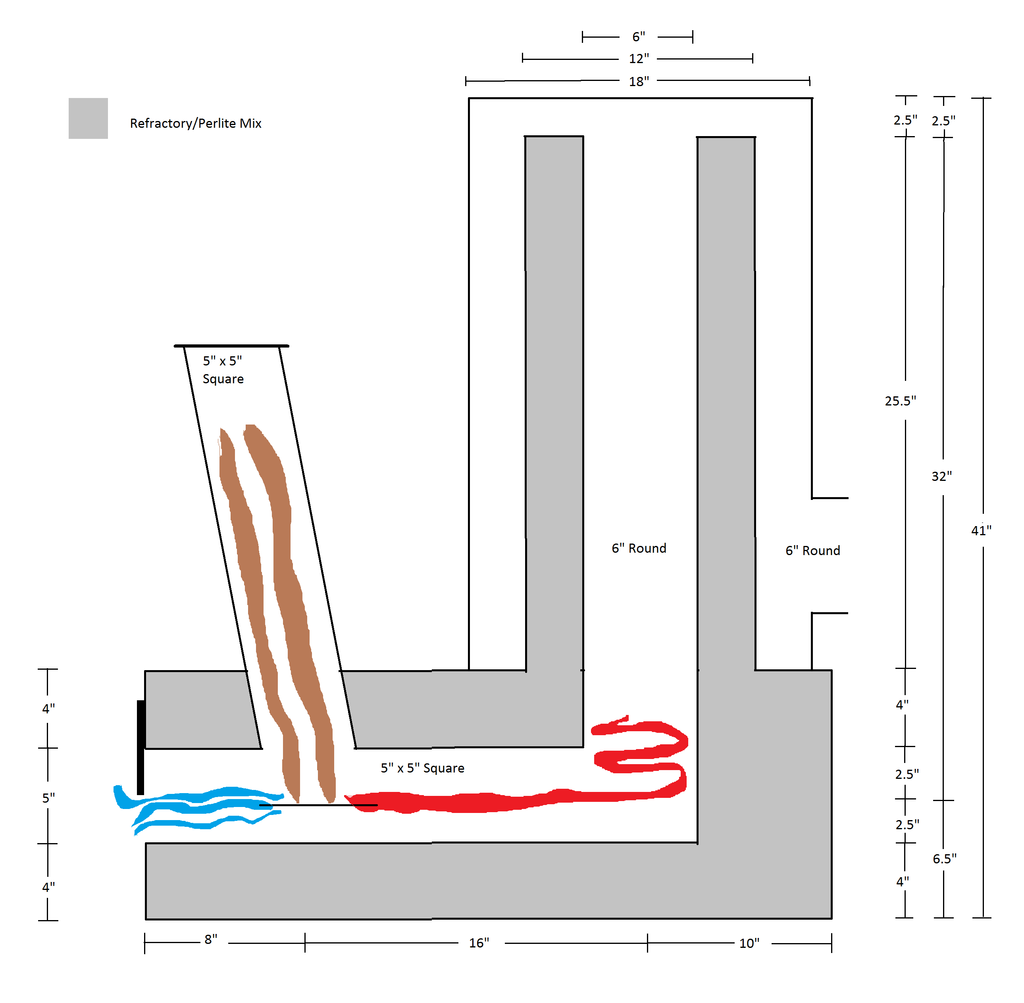

Glenn Herbert wrote:I'm sorry, but you seem to have misunderstood the way a RMH core with the 1:2:4 proportions is supposed to work. The 8" dimension is the vertical wood feed AND air intake; the 16" and 32" dimensions are correct. There is no front air intake. Also, the feed works better completely vertical than slanted.

Glenn Herbert wrote:

If you think that a front access port is needed for ash cleanout, I can assure you that it is not (unless maybe you have gorilla-sized arms). I have cleaned a 6" x 6" J-tube with my bare hand, and with a sardine can on a short handle, easily.

Glenn Herbert wrote:A 5" x 5" core would be trickier, but for a 6" duct size system, a 6" x 6" core would be fine.

Glenn Herbert wrote:Can you give us any information about your plans for the system? What kind of mass, how long, what size of space and how insulated, how you use the space, what your climate is like?

Glenn Herbert wrote:It may be helpful to explain that having the wood feed capped off and air coming from the front will let the wood get hot and char up into the feed tube. When you open the cap to add more wood, you risk a puff of smoke or even flame bursting out of the top and singeing your eyebrows off. The air intake pulling down from the top keeps all the fire and smoke moving in the right direction, and you can clearly see when you need to add more wood.

Glenn Herbert wrote:The 16" burn tunnel dimension is a maximum, and if your barrel clearances allow, you can make it shorter and get better draft.

Glenn Herbert wrote:Keep the feed vertical, though. The best method I have found (also recommended by everybody I have read) is to lean the sticks away from you so that they lean against the burn tunnel roof, and air has to go down on your side of them or through and between them to get to the fire. This keeps the tops of the sticks a bit cooler and helps preheat the air. If you lean the sticks back toward yourself, the air can flow down on the far side of them and leave some of them starved for air, while a lot of air goes into the burn tunnel without meeting the burning coals.

thomas rubino wrote:That's not a bad price for refractory. Way more than fireclay but should be more durable than the FC mix Your going to want to experiment. Try a small batch at 50/50 then try a batch at 70/30 I think a 50/50 mix might be to fragile in the feed tube but be fine in the burn tunnel and riser. The fireclay mix is known for wear issues in the feed tube (trying to push wood down) When casting a core you should be able to vary the amount of perlite, using a refractory heavy mix at the feed tube end and then add more perlite as you form the burn tunnel . The riser can be cast with a "fragile mix " heavy on perlite.

Glenn Herbert wrote:I would suggest making a richer refractory mix for the inner surfaces of the feed tube and burn tunnel, and surrounding that with a highly insulative mix.

Glenn Herbert wrote:The riser can be mostly perlite with just enough refractory to hold it together (make test bricks with various ratios).

Jay C. White Cloud wrote:

Good luck and if you really need to, give me a call...these long emails kill me as I tend to be long winded.

Regards,

jay

Rufus Laggren wrote:our at least an overview and some understanding of what kind of process you're getting into and the different viewpoints, motivations and constraints on the participants.

Some general rules of thumb:

1) The way it starts (with any associate) is the way it's going to continue. Forewarned.

2) Expect and budget your time to talk with a LOT of people. When you can't personally develop total expertise in a particular area you must rely on as much research as you can afford and then spend time talking with at least three and as many as 7 or 8 contractors (or other people) in that field. Talk with as many people as you can afford the time for and take good notes so your time is well spent. You start to see common threads, agreements, recognize certain types of business practices that you like (or don't); you also develop a feel for and start to recognize people who a) _know_ what they're talking about (not all that common actually, even w/a major degree after their name); b) Are willing and able to work with you in a worthwhile way; c) evince good business practices that you can have confidence in; d) relate well with you.

If you can't be deeply involved (it will consume your life for the duration of the project) you may want to use the services of a management agency to monitor the job of the GC. This is not a very satisfactory situation - it's expensive and it _will_ involve some conflicts. But if you can't spend the time needed to oversee the job on at least a weekly basis it's something to consider. Again, read some books about the residential home building process to pin point alternatives and key players that might help you.

If you work directly with the GC, expect to visit the job site at least weekly and inspect everything carefully as you can. You _must_ raise issues you see and get them remedied or clarified to your satisfaction as soon as possible - that's _your_ job and it's a LOT of work. You need to have at least bi-weekly milestones and generally conform to good project management process - you _need_ to know when there's a problem to attend to. The specific methods you use to manage the project (manage the GC) depend on you and the GC but you must actively manage it IMHO. You will likely spend 15 to 20 hours a week (if you're working a "day job" full time, otherwise a lot more) on this and other aspects of the build for some months preceding the build and some months after the job is technically finished - as well as during the actual build. Try very hard spend a couple hours a week personally inspsecting the jobsite. You're not an engineer or architect or builder so you don't expect or try to confirm _all_ the details of a build; that's not realistic.. But you _can_ look closely at everything, focusing on the latest issues and milestones, get an overview of the job, show the GC and others that you _are_ most interested and paying close attention and perhaps most importantly give yourself a feel for the actual physical house which in turn will influence your real time decision making. And of course you will often see things that don't line up with your expectations and need a little clarifying.

Nobody got this far in life w/out having some smarts and you absolutely have the right and the need to apply any and all intuitions, skills, training, energy and any other advantages you might accumulate to this project. You more or less owe it to the house and yourself and the world in general. You mention your wife and if she can join actively in the project you'll be way ahead. Don't hesitate for one second to play good-cop bad-cop with the people you have to work with. Only remember they're human too and we're all in this together.

Best luck. It's a damn fine challenge and you're sure to learn a whole lot.

Rufus

R Scott wrote:You are ONLY out a couple grand and a couple months now. Once you are in the middle of a build, you can be out A LOT MORE--tens or hundreds of thousands and years of time can be lost to a bad GC (or sub). Been there, done that. I know many that lost everything because the builder shafted them and then the bank took the land to recoup their losses.

R Scott wrote:You need to be 100% in agreement with how the GC has built other homes, because most don't like to do anything different--not out of pure stubbornness but a matter of "stick with what works" when money is on the line. They are liable if your ideas don't work in many states. In the same vein, you need to listen (not necessarily follow, but consider carefully) to the experts as they know more of local conditions and experience of past failures in the area.

Brian Knight wrote:Hmm funny you should say that about builders. Ive heard IT folks are like professional engineers and should be avoided because they are too difficult to work with.