Here is a little info regarding pollarding trees. While I understand that there are a few different understandings of what pollarding encompasses but this is basically the

International Society of Arboriculture's accepted practices for properly pollarding a tree.

First off the difference between pollarding and coppicing:

Coppicing is practice of cutting a tree or shrub to very near the ground in an effort to cause the plant to generate many new shoots mainly from dormant buds in the roots and along the root flare of the stump. One of the main advantages of coppicing vs. pollarding is that decay of the main stems that are cut is not an issue because they aren't actually supporting the new flush of growth, the existing root system is supporting that new growth directly.

Pollarding is the the practice of

repeatedly cutting a tree or shrub back to the same point(s) according to a regular schedule

with the goal of maintaining the main stem(s) below the cuts in good health and encouraging the stimulation of adventitious buds very near the cut area. One of the main distinctions between pollarding and coppicing is that fact that pollarding implies regular scheduled maintenance over the life of the plant whereas you

can coppice a plant only once. The other difference is the desired goal of maintaining the stems below your cut in good health. This makes pollarding for true long term success much more demanding than coppicing.

Please don't confuse a slow tree death due to repeated topping with true pollarding of the tree. When done properly to the right kinds of trees it's been shown to greatly increase the lifespan of the tree. When done improperly or to the wrong kind of tree it will always lead to a shortened lifespan of the tree.

To be done properly you must decide to begin the process when the point you wish to cut back to is still relatively young. From

Francesco Ferrini's study on pollarding:

A tree responds to pollarding by building a

dense mass of woody fibres around the cutting

points. This bulky mass resists decay and

effectively divides the vigorous juvenile growth

from the aging stem (Harris et al., 1999). Hence, the

defensive and structural integrity of the tree is

maximized using this pruning system because

pruning cuts are made when biological reactivity of

the trees is quite high and living cells quickly react

to wounds and environmental changes and can

develop a strong defensive reaction (Coder, 1996).

Also, pollarded trees develop a constantly

rejuvenated, energy-creating young canopy, on top

of an increasingly ancient trunk. This slows the

tree’s normal aging processes.

The older the tree is the more you will be limited as far as where you can cut the tree back to and expect it to recover properly. A healthy young tree can handle being cut back to a single trunk where a mature one will surely succumb to decay if you try the same thing.

Once you pollard a tree it is vital that you cut all the shoots back to the pollard "head" (sometimes called the pollard fist) at least every few years, preferably every year or two. This prevents the shoots from maturing to the point that there is a chance of decay setting in before the tree can

compartmentalize the wound. It is also vital that you do not cut into the pollard head; focus on making

proper pruning cuts but it is better to leave a little bit of a stub if you have to to avoid damaging the pollard head.

As far as timing of the actual cutting, it is best to do the cutting when the tree is in its dormancy.

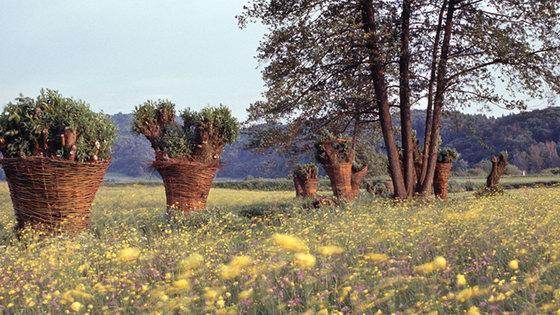

Some proper pollarding examples:

Some not-so-great pollards:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-hlh_CwkfRyw/UcDIaaObHSI/AAAAAAAAAVU/FyonGYmYGiI/s1600/pollarding.jpg

http://www.salisburywatermeadows.org.uk/images/friends/news/willow.jpg

The biggest mistakes I tend to see when it comes to pollarding trees would be cutting to point on too mature of a stem, cutting at the wrong time of year (a big risk of sunscald killing large portions of branches/stems when removing all the canopy) and cutting into or behind the pollard heads during pruning.

5

5

4

4

![Filename: 2-Willow-pollard-in-May-.jpg

Description: [Thumbnail for 2-Willow-pollard-in-May-.jpg]](/t/42620/a/24078/2-Willow-pollard-in-May-.jpg)

3

3

4

4

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2