miles mccoo wrote:

thank you, Jennifer, for an excellent answer

Miles - thanks for posting the questions - it got my brain working!

miles mccoo wrote:I have some followup questions.

On ponds. I really want some water on the property for my kids. I'd like to go to the eastern parts of the state because I can get more acreage and there are more available choices. If a pond really is out of the question in the OR/WA dessert areas, then I'll have to look more at the western parts.

Also on ponds, it seems from watching Holzer stuff, that his first answer is always "gotta put in ponds". Ask him if I should get a an Adobe house or a Craftsman, his answer will be "does it have a pond". It is just because he's way more talented at the pond thing than I would be?

I can appreciate wanting water in the form of a pond for the kids - what a beautiful feature to grow up around! On the rain shadow part of the state (east), you may have a harder time with a pond than on the western side of the mountains. One of the reasons why you can get so much more land for the same price is because of the water situation, as I'm sure you know. I would definitely ask some longtime locals in the area you want to buy into what their impression is about putting ponds in. Where is the water coming from, what kinds of problems do they have (if any) with ponds, what kind of

evaporation rate do they have, etc. And I guess the most important factor - where's the water coming from? If you're on a slope, is there somewhere uphill that you can catch the water? Do you control it or is it owned by someone else? I know Geoff says to start swaling as high in the landscape as you can. As you get lower in the landscape, more and more water is available due to gravity, so the most likely places for springs popping up and having enough water for ponds available is lower in the landscape.

Oh, and I'll admit right now that I do not know Holzer's work very well so I cannot speak to what he does. I've read

Fukuoka and while I greatly admire what he did, even he admitted that some drylands were more challenging than others. Mostly he worked with areas where there was an existing stream or river and swaled out from them (at least this is my understanding). Lawton takes it a step further and looks to the landscape to find out how the water flows. He actively seeks out good positions in drylands - one with some kind of catchment he can build on like wadis or even road surfaces. I know our own local expert, Brad Lancaster, does the same. Not all positions in a dryland are going to be favorable for production like you speak of - you'll want to choose carefully.

miles mccoo wrote:fruit trees vs support species. I'm happy to do the 10:1 thing. I also know it would take a couple years to get to bearing age, so I wouldn't want to wait to even plant. Is it enough to plan similar sizes seedlings (or seed as Paul advocates) in these ratios?

Drylanders have a saying, "Plant the water before the trees". This means using water harvesting techniques appropriate to your situation.

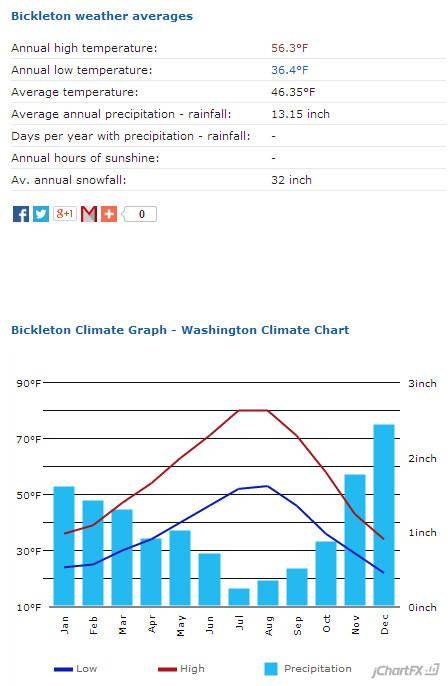

miles mccoo wrote:last, Arizona climate is a bit different from what we have here in WA and OR. how much does that factor? Portland area gets 39"/year; way more than is needed to grow anything. 13" is about a third of that. 8" is 50% less again.

Yep - our climates are different - which is why it's so critical to talk to the locals. Also you might enjoy this podcast done by Paul and Geoff Lawton where they talk about high deserts:

https://permies.com/t/33750/podcast/Podcast-Geoff-Lawton-Part

miles mccoo wrote:I suppose my question is a matter of how much is enough for most things? 39" is more than needed. maybe 30" is on the threshold, but you can go down to 20 if you do swales. 8 is enough if you've spent some years adding organic matter and shade. Adding a berm against the wind would give some more margin. Probably not linear. My point is not that I want an exact formula. I'm looking for an idea of how challenging the OR/WA dessert areas really are.

I get what you're trying to ask and it's a really valid line of inquiry. And to use the old permaculture stand-by - "it depends" (dontcha love it?).

One of the things I teach my students is that they need to first identify their limiting factors and then design for them by using appropriate techniques and strategies. So it sounds like where you are, your limiting factors are going to be: low rainfall (especially in summer), probably a fairly high evaporation rate due to altitude and wind and some heat, the wind itself, possibly your soils are more alkaline and may lack organic matter. I'm not familiar with that area so there may be other factors as well.

The profile of the land will also matter - is it sloped? If so how steeply? Usually anything above 18 degree slope is not good for swales and should just be put into forest (according to Lawton and Brad Lancaster), unless you want to spend the time and money to terrace it. Or is it flat? Or some of both? You might have a combination of the above so your techniques would vary depending on the land profile.

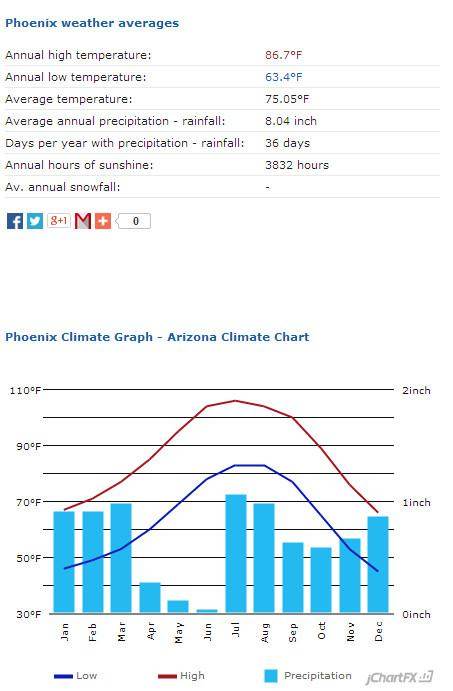

I think one of the questions you're asking is how many inches of rain do you need to grow stuff successfully. It depends on what you're trying to grow. I'm going to give you some stats from the Tucson/Phoenix area for comparison. I don't have these numbers for your area but maybe your local Ag Ext office will have them.

Brad Lancaster has classified plant water usage into 5 categories depending on how many inches of rain it needs for 1 square foot of planting area.

--Very High = 65" of rain per square foot. This includes vegetable gardens, specifically sunken and mulched vegetable gardens (the most water wise in our climate - if you do raised beds, this number will go up)

--High = 43" of rain per square foot of canopy. For us in southern AZ, this includes all citrus varieties and loquats.

--Moderate = 30" of rain per square foot of canopy. This includes most deciduous fruit trees and date palms.

--Low = 16" of rain per square foot of canopy. This includes pomegranates and jujubes.

--Very Low = 7" of rain per square foot of canopy. This includes mostly native legume trees.

With only 8" of rain per year, only native trees would survive without additional water. By catching water, holding it in the soil in infiltration basins (flat land) or swales or keylines (sloped land up to 18 degrees), we can start upping our game to some of the "low" water use trees. Keep in mind that you have to have surfaces to catch water from. Once we have water soaking into the soil (sometimes even getting it to soak in is challenging here), we do everything possible to stop it from evaporating off. Our evaporation comes primarily from heat and very dry air. Wind is not that much of a factor for us. An open area like a pond is just asking to be evaporated.

Another thing to consider is that if you plant trees, they act as pumps for the water in the soil. Having trees is critical for the hydrological cycle but keep in mind, it will slow down the formation of springs and ponds. Consider that when people clearcut forests, suddenly the streams are overflowing and the ponds and lakes overflowing their banks because a lot of water was held up in the "hydraulic pumps" we call trees. This abundance quickly recedes though, and then the land starts to become desertified because a critical element is missing - trees. So by planting trees that are appropriate to the amount of water you can harvest, you are benefiting your watershed, BUT it may take longer to build naturally occurring springs and ponds.

miles mccoo wrote:Phoenix gets 8 inches, one of the towns I'm looking at gets 13. Also Phoenix is hotter by 20 degrees in the summer. Given that, does the problem change from "a real challenge", to "it's not too bad if you follow some basic principles"?

It all depends on your limiting factors, land profile, exposure, access to water, what you want to accomplish and how much patience you have. Drylands take longer but the net results are probably the most stunning of any permaculture application.

Sorry if I rambled and repeated - too many interruptions! Hope this made some kind of sense.

2

2

1

1

1

1

But I seem to gravitate towards deserts because this is where I feel I can make a difference. I've lived in MI and WI - super easy to grow stuff there, abundant water but COLD AS HELL. No thanks. I like the hot drylands.

But I seem to gravitate towards deserts because this is where I feel I can make a difference. I've lived in MI and WI - super easy to grow stuff there, abundant water but COLD AS HELL. No thanks. I like the hot drylands.