posted 13 years ago

Hello again, Kari,

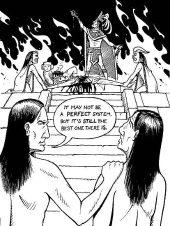

You wrote, "Are there ways to provide long term security and a sense of ownership / reward / belonging if you aren't ready to share the actual ownership of the land?" Yes, fortunately. The first thing I advise people to do when they want to do this is to not call it an intentional community. Call it anything else, but don't use the C word. Because using the C word will set people up -- consciously as well as emotionally-unconsciously -- to have expectations about it that won't be realistic. Call it a shared homesite. Call it a shared farm. Call it Jack. But stay away from the ********* word.

Because when people move to "a community" or "join a community" they're likely to feel put off or put down or put-upon if they don't have more decision-making rights than they actually do. Or more of sense of ownership or sense of entitlement -- watch out for that! -- than they acually do. But call it something simple, descriptive, and accurate, like "your place on our farm," and their wily and devious unconscious mind probably won't go doing that thing minds often do. Which is to project onto you, your farm, and your whole shared experience, the unconscious, unnamed, and unknown expectations of what "community" means emotionally to the little kid part of them that's stlll in there. Still in there with emotionally charged unmet needs that some part of them thinks living in "community" will finally, at long last, fulfill. I'm not putting them down; this is just how human nature seems to work!

So the first thing to do is let people know you're hoping for congenial folks to share the land with. Describe the kinds of things you'd like to do together, such as, say, shared meals, work parties, gardening, other homestead tasks and benefits. That is, describe your envisioned activities together, not the fact that it would be a "community." What you'd be looking for, I'm guessing, are land-sharing pals who, together with you and your family, create a community-like atmosphere. Then you could have exactly what you're looking for -- nice folks to share the work and the rewards with, and . . . a sense of community.

The French cuisine teacher Julia Child did this with her husband Paul for 30 years in France. Her best friend Simca and her husband Jean had a farm in Provence. They said, "Hey, Julia & Paul, why don't you build your own house over there on that side of our field. You pay for it and live in it for as many years as you want to. And if you don't want it anymore, just move out and we'll own it." So that's what they all did. No property changed hands, no deeds. What Julia & Paul paid for was the cost of building the house, which with each passing decade became a better deal, as they didn't pay any rent. These four friends enjoyed a sense of community with each other for 30 years and didn't call it by the communauté word once.

I'm not necessarily suggesting this as the exact form or agreement. But just to give you an idea of one way it could work.

Who you get, and how you get them, visit with them, interview them, screen them, ask for and call references etc, and make a written, that is, written (did I say written?) agreement with them, has everything to do with how it works out over time. I learned a tip from two different sets of community friends, one in Portland and the other in BC. They each learned, um, the hard way, not to advertise that they were looking for people who wanted to join a community. Because when you do that, you might get some folks who are doing fine and will work out well, as well as some basically lost souls who are yearning for some something (emotionally charged unmet needs that they [subconsciously] think community will finally fulfill). And they tend not to do well in community. BUT, said my two sets of friends -- who didn't even know each other -- if you advertise for people with the qualities and skills that you're looking for, and for the kinds of activities and roles you have in mind, then you're likely to get wonderful folks who can do community living just fine.

Because people who don't need community can often do very well in community. And people who are desperate for community often have a disruptive effect in the community because their neediness doesn't go away once they move there.

OK, so my two friends each advertised in essentially the same way, "Seeking happy, confident, mature folks to help us manage an organic garden and goat milk operation on a rural sustainable homestead." Voila! Fabulous candidates applied.

I have a workshop handout, "A Clear, Thorough Membership Process," which I'd be happy to send you. And anyone else reading this post who'd like it. diana~at~ic.org It tells more about all this.

About the issue of ownership, not buying in, the dynamics of that, I wrote about that in Chapter 3 of Creating a Life Together. I'd reprint it here but the text is buried in another computer in some old and creaky software. So, if you can get ahold of the book, and libraries have it, and Amazon has real cheapused copies -- but of course the best is your local independent bookstore -- well, it's the section in chapter 3 called "When You Already Own the Property."

One more tip before I leave off all this fast typing, I highly recommend a document, with copies for you, for them, for the file cabinet -- and a big chart of all this on your dining room wall -- of your explicit rights and responsibilities as owners, and the rights and responsibilities you don't have, and the other party's (tenants? renters? ongoing guests?) explicit rights and responsibilities and the ones they don't have. So that your arrangement is crystal, crystal clear. So that neither you nor they can ever say, "But you promised we could . .. !" "But you implied that you would . . . !" Because you agreed on these things in advance (including how you could change the agreement by mutual agreement) and were crystal clear and up front about it.

One reason people can have awful, awful conflict in communities -- and in shared homesteads -- is not because of what they agreed on necessarily. It's because whatever they agreed on wasn't clear enough to all parties, who should have all signed it, kept copies. and had copies right on hand so they could look it up any agreements anytime. I'm a fanatic on this, actually.

Well, enough for now. Thanks for the great question. And good luck!

Diana

1

1

1

1