Thanks for the notice, but I'm hardly a legal expert.

yes, we often start with small earthworks.

but, as I think was also pointed out by Bill,

"small" clearings for hippies camping out... then building and gardening ... then inviting their friends out to form a community ... created the pockmarked holes in a vanishing stand of Australian rainforest, nominally protected as a public trust.

Rabbits are small. So are goats.

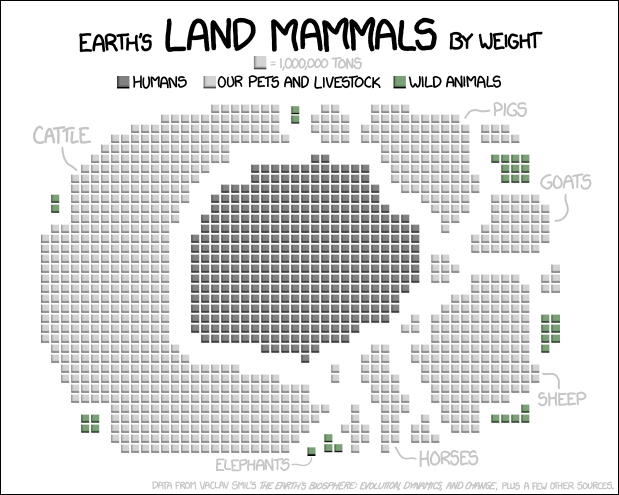

So are cows, compared to elephants:

And yet the total number of cows is only slightly greater than the total number of people; and I suspect each cow has a far smaller environmental footprint than each person. Cows merely walk and graze; people also drive and plough.

Given our place on the XKCD.com diagram above, we have a certain responsibility to make sure that even the small changes we make to our local environment, are beneficial rather than harmful.

It's a scary point in history to be alive, but potentially a very important one.

This multiplication of impact is why I'm still staring at most of the black plastic around the pond, and poking around at the edges, rather than renting a bulldozer. I know that I don't know how to operate the pond, the landscape, (although I'm getting closer to being able to operate the bulldoze

).

I only know that it looks ugly to my eyes, and I've made some small-scale efforts to improve it. These have not necessarily turning out as planned. Not bad, not worse perhaps, but not as planned, and not necessarily much better. I have discovered a number of things that I didn't notice 3 years ago, or 2. I'm hoping that with more education, and more small trials, I can find a way to make things better without making them worse. Because the pond up here seems a very precious thing.

Meanwhile I'm still driving back and forth to social and work and medical destinations. All that incurs costs, too; I see oil in the meltwater, and cringe. Don't know if oyster mushrooms will survive up here. Know I can't, without contact with other people. I have not yet made enough friends up here to have any confidence in surviving without a car.... in fact I'm not sure it's a livable place without a car, unless you are really dedicated to living like a Sherpa. And that takes a lot more land and sheep than I have ... and see above about the world having a finite amount of land, and a lot of it is already holding sheep.

blah blah blah ... paralysis ...

I think the biggest thing is to start with something that is messed up, somehow - a degraded farm, urban lot, over-grazed or logged-out patch of backwoods. Then you can work on building that back to at least the level of abundance that the surrounding wilderness shows. But so often, my first few guesses as to what is "wrong" are wrong. My ancestors did the same thing, trying to improve on what was there, and their efforts gave rise to what's here today.

So it's important to start with broken, take it apart, fix it, and keep doing that until you can fix it so it works. Like the old-fashioned kids' method of learning about radios, alarm clocks, watches. Don't take apart a working one until you absolutely have to - but you can keep working on broken ones, until you are confident you can improve a working watch that just is running a little slow, ... but even an excellent watchmaker is going to be very cautious about peeking inside a watch that's working.

And unlike a watch, nature has some very complex and difficult-to-understand functions, and we may not always be clear that it's already working, or how.

Bill did mention this earlier, see the discussion in the main thread about Type 1 error: Leave the bush alone. Don't break into intact wilderness - it's working great, there's too little of it left, and we need it as a manual for understanding what's going on in the rest of it. And I believe he said something about your needs will be in conflict with so many other things that you will need to commit a great deal of destruction to meet your needs.

Yet a lot of these chapters read like manuals for how to start fresh - and a lot of people's idea of 'starting fresh' is a plot without any buildings or signs of human activity .... in other words, intact wilderness, or something that looks a lot like it to our novice eyes.

I would love to have a "before" and "after" plot for each improvement suggested - showing why that site called for that technique.

I think greening the deserts is another place that this type of invasive management really shines - especially old-world deserts that clearly show ongoing human involvement. As long as you do little patches, not whole regions, the lizards probably don't mind moving two hot rocks over and having a few more insects to choose from.

-Erica

1

1

2

2

1

1

).

).