4

4

2

2

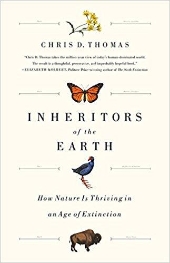

“It is contrary to all evidence to suppose, as a few writers have, that in time invasive species will settle down with native species into stable “new ecosystems.”

“Clearing a forest for agriculture reduces habitat, diminishes carbon capture, and introduces pollutants that are carried downstream to degrade otherwise pure aquatic habitats en route. With the disappearance of any native predator or herbivore species, the remainder of the ecosystem is altered, sometimes catastrophically. The same is true of the addition of an invasive species.” (my emphasis).

"HAWAII. The Hawaiian archipelago, like the equally far-flung Easter, Pitcairn, and Marquesas archipelagoes, deserves mention in part for what it once was. Its tropical climate, relatively large size, and mountainous terrain with multitudinous habitats promoted the genesis of a large diversity of land-dwelling plants and animals. A high percentage of these originated as products of adaptive radiations. Dramatic examples of such species swarms include the honeycreepers among the smaller birds, tree crickets among the insects, and lobelias among the flowering plants. The beautiful assemblage has been largely wiped out or pushed into the remote uplands of the central mountains by agricultural conversion and semiwild gardens of invasive species. Perversely, the latter have become a poster child for the “novel ecosystems” celebrated by Anthropocene supporters." - My emphasis

The only solution to the “Sixth Extinction” is to increase the area of inviolable natural reserves to half the surface of the Earth or greater.

it also requires a fundamental shift in moral reasoning concerning our relation to the living environment.

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

2

2

"People may doubt what you say, but they will believe what you do."

Idle dreamer

Todd Parr wrote:

I fully agree that humans need to be taking up less space on the planet. This can only be done by population control. I'm all for that, but I believe it isn't a viable solution until things get far worse than they are now, simply because you would never get people to agree to it.

Idle dreamer

Tyler Ludens wrote:

You mean you would never get men to agree to it. The most effective method of population control is full human rights for women including the right to her own body and reproduction. http://www.populationconnection.org/resources/health-human-rights/

"People may doubt what you say, but they will believe what you do."

Todd Parr wrote:I'm certain you have researched this and feel much more strongly about it than I do, but some of these things to me are outright guesses.

"Wilson explains the Law of Tens. One in ten introduced species will jump the fence and become what I call a garden escape. One in ten of those will become a problem. "

Is there any evidence at all that one in ten introduced species that escape will become a problem? Also, in my mind, no one has clearly defined "introduced species", so any possible number that a person can come up with is worse than a guess. There isn't even a basis to guess from.

Todd Parr wrote:

How can you possibly keep plants from "novel ecosystems" from spreading into wildlife habitats?

I don't believe it is possible to ensure that no "invasive species" can ever "jump the fence". None of us lives in a bubble, and keeping a perfectly clear delineation between the areas we cultivate and wild areas is just not possible.

So much of the surrounding land is already down to eucalyptus, and it's hard to imagine much being worse than that stuff. ... The bits that are screaming out for modifying are bits that are smothered in cistus, growing around the edges, preparing the land for tree cover. ... There is loads of acacia growing wild here, which I think was introduced for land restoration purposes. ... But it's illegal to plant it, so I don't know how you balance all that up. It also shoots up from the roots in great thickets if you try to cut it down.

Todd Parr wrote:

I fully agree that humans need to be taking up less space on the planet. This can only be done by population control. I'm all for that, but I believe it isn't a viable solution until things get far worse than they are now, simply because you would never get people to agree to it.

Todd Parr wrote:

"Permaculture" seems to me to be trying to go in the direction of rebuilding areas that have been destroyed, or nearly so, by planting very diversely, minimizing outside inputs into the area, and trying to create an place that is as self-sustaining as possible. If planting food forests, conserving as much water as possible, minimizing or eliminating chemical use, etc., aren't the answer, someone needs to come up with a better one, rather than telling everyone that their best effort is just making everything worse and anything we plant that isn't strictly "native" is going to cause another great extinction.

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

Todd Parr wrote:

Tyler Ludens wrote:

You mean you would never get men to agree to it. The most effective method of population control is full human rights for women including the right to her own body and reproduction. http://www.populationconnection.org/resources/health-human-rights/

I haven't looked into the issue, but I know one man that you can certainly get to agree to it.

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

yet invasives causing problems not sure how many . Do all invasives cause problems ? ( penny wort , knot weed , balsam , rhodadenrum ) ( I'm just talking plants animals for me are a different discussion )

yet invasives causing problems not sure how many . Do all invasives cause problems ? ( penny wort , knot weed , balsam , rhodadenrum ) ( I'm just talking plants animals for me are a different discussion )

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

David Livingston wrote:

As for turning over 50% of the world to nature this to me harks to the idea that nature is static

Idle dreamer

1

1

2

2

1

1

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

1

1

Neil Layton wrote:

We are now entering what looks like the Sixth Great Extinction on this planet, and humans are responsible. I'm horrified to discover people here who are not only indifferent but seem to want to make the problem worse.

"People may doubt what you say, but they will believe what you do."

3

3

Steven Kovacs wrote:Suggesting that evolution will sort it all out doesn't seem to fit the evidence.

"People may doubt what you say, but they will believe what you do."

1

1

Todd Parr wrote:

Steven Kovacs wrote:Suggesting that evolution will sort it all out doesn't seem to fit the evidence.

Evolution has done a pretty good job of supporting life for millions, if not billions, of years on this planet. I believe it will continue to do so, long after humans are gone.

1

1

"People may doubt what you say, but they will believe what you do."

7

7

Neil Layton wrote:Organisms live in communities. They are often co-adapted to live in these communities (natural selection is driven by the organism's adaptation to its environment, not some "survival of the fittest"

Neil Layton wrote:You cannot just switch out one species for another species without consequences for the rest of the community.

Neil Layton wrote:there are plenty of species that can enter a community and develop relationships with the species already living in it.

Neil Layton wrote:There are a few - and this is only predictable to a point and depends on many factors, mostly having to do with the existing community - that take over, become a monoculture and cause extinctions.

Neil Layton wrote:This is why, the further from its evolved ecological area a species originated in the greater the likelihood of it tending to monoculture

Neil Layton wrote:To suggest that these are going to settle down and develop some fluffy bunny new ecosystem without wrecking the diversity of the community is contrary to all experience.

Neil Layton wrote:I know that there are people out there who believe in this "balance of Nature" stuff (although part of the definition of "ecosystem" involves the word "dynamic"), but if you push that balance far enough, you get a tipping point, and tipping points are where you get widespread extinctions.

Steven Kovacs wrote:the fact that extinctions are vastly outpacing speciation is a serious problem. .

2

2

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

Idle dreamer

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

1

1

Idle dreamer

)dont like being around humans :

)dont like being around humans :

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

2

2

1

1

2

2

1

1

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

2

2

Idle dreamer

1

1

Idle dreamer

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

2

2

Idle dreamer

Seeking a long-term partner to establish forest garden. Keen to find that person and happy to just make some friends. http://www.permies.com/t/50938/singles/Male-Edinburgh-Scotland-seeks-soulmate

| I agree. Here's the link: http://stoves2.com |