Justin Rhodes 45 minute video tour of wheaton labs basecamp

will be released to subscribers in:

soon!

john mcginnis wrote:Have you considered a propane infrared heater? They are reasonably efficient, generate a contact heat and are quiet and its not electric. You just need to assure adequate ventilation.

1

1

Luke Townsley wrote:

Any thoughts?

My project thread

Agriculture collects solar energy two-dimensionally; but silviculture collects it three dimensionally.

Moderator, Treatment Free Beekeepers group on Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/treatmentfreebeekeepers/

1

1

Michael Cox wrote:Yes, why not get the hens to do it for you?

2

2

Paul Ewing wrote:

One method that we reduce your electric lamp requirements is to use a hover type brooder like the one presented by the Ohio Experiment Station. See Ohio Experiment Station Electric Lamp Brooder for information on building one. They need approximately half the wattage of a normal brooder house. I just built a larger 4x8 foot one for 300 chicks. It would work fine for 500-600 chicks. These also work well in colder weather without having to heat the entire brooder house. During the development they tested brooding chicks in a walk in freezer using just two 250W lamps in a 4x4 brooder.

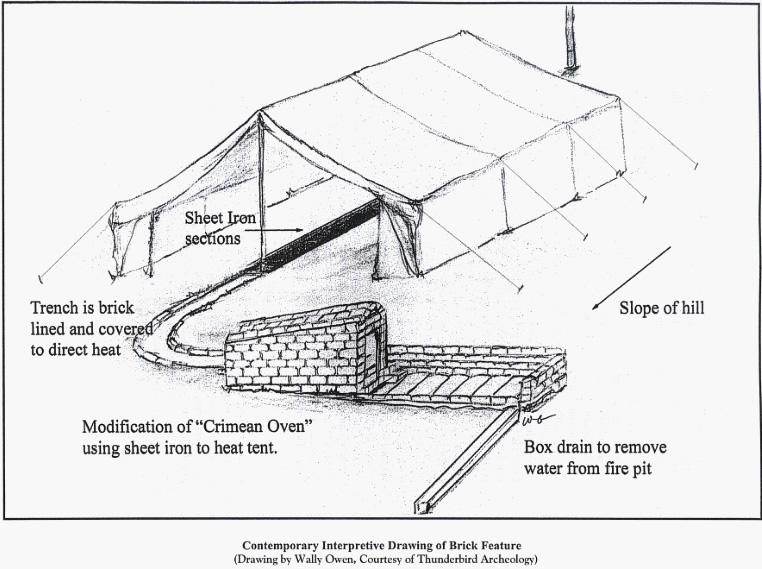

Joe Braxton wrote:Perhaps this will give you some ideas -

"Civil War Crimean Ovens" - http://alexandriava.gov/historic/archaeology/default.aspx?id=39470

Replacing the "oven" with a rocket stove might be the way to go. Hope this will help.

Moderator, Treatment Free Beekeepers group on Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/treatmentfreebeekeepers/

Paul Ewing wrote:That is a lot of broody hens to coordinate and in my experience, the survival rate for chicks under hens is 50-60% at best.

My project thread

Agriculture collects solar energy two-dimensionally; but silviculture collects it three dimensionally.

Michael Cox wrote:On your scale it makes more sense to take control I guess.

Regarding the rocket heated tent plan - I wouldn't touch it for brooding chicks. You have no where near enough control over the temperature, either too hot or too cold, and the time needed to find tune it (not to mention the risks of losing whole batches of chicks) makes it pretty much a non-starter in the this scenario.

Electric brooders, thermostatically controlled give you the ability to fine tune your setup with ease, and provided your power supply is reliable you should have no problem with continuity of power. Who wants to feed a rocket stove twice a night for a month?

1

1

Peter Ellis wrote:I would think the link Paul Ewing provided makes lots of sense. Not the first time I've seen that essential system, and I am pretty sure I've seen it discussed using lower wattage lamps. Seems to me much more efficient than trying to use an aquarium heater.

I see an awful lot of time and effort being put into developing and perfecting some sort of stove system, so much that it would be a net loss of time, money and energy compared to sticking with a simple, proven electric method like the hover box with flood lamp(s).

1

1

1

1

Find me at http://www.powellacres.com/

2

2

At this season of the year Chinese incubators were being run to their full capacity and it was our good fortune to

visit one of these, escorted by Rev. R. A. Haden, who also acted as interpreter. The art of incubation is very old

and very extensively practiced in China. An interior view of one of these establishments is shown in Fig. 96,

where the family were hatching the eggs of hens, ducks and geese, purchasing the eggs and selling the young as

hatched. As in the case of so many trades in China, this family was the last generation of a long line whose lives

had been spent in the same work. We entered through their store, opening on the street of the narrow village seen

in Fig. 10. In the store the eggs were purchased and the chicks were sold, this work being in charge of the women

of the family. It was in the extreme rear of the home that thirty incubators were installed, all doing duty and each

having a capacity of 1,200 hens' eggs. Four of these may be seen in the illustration and one of the baskets which,

when two−thirds filled with eggs, is set inside of each incubator.

Each incubator consists of a large earthenware jar having a door cut in one side through which live charcoal may

be introduced and the fire partly smothered under a layer of ashes, this serving as the source of heat. The jar is

thoroughly insulated, cased in basketwork and provided with a cover, as seen in the illustration. Inside the outer

jar rests a second of nearly the same size, as one teacup may in another. Into this is lowered the large basket with

its 600 hens' eggs, 400 ducks' eggs or 175 geese' eggs, as the case may be. Thirty of these incubators were

arranged in two parallel rows of fifteen each. Immediately above each row, and utilizing the warmth of the air

rising from them, was a continuous line of finishing hatchers and brooders in the form of woven shallow trays

with sides warmly padded with cotton and with the tops covered with sets of quilts of different thickness.

After a basket of hens' eggs has been incubated four days it is removed and the eggs examined by lighting, to

remove those which are infertile before they have been rendered unsalable. The infertile eggs go to the store and

the basket is returned to the incubator. Ducks' eggs are similarly examined after two days and again after five days

incubation; and geese' eggs after six days and again after fourteen days. Through these precautions practically all

loss from infertile eggs is avoided and from 95 to 98 per cent of the fertile eggs are hatched, the infertile eggs

ranging from 5 to 25 per cent.

After the fourth day in the incubator all eggs are turned five times in twenty−four hours. Hens' eggs are kept in the

lower incubator eleven days; ducks' eggs thirteen days, and geese' eggs sixteen days, after which they are

transferred to the trays. Throughout the incubation period the most careful watch and control is kept over the

temperature. No thermometer is used but the operator raises the lid or quilt, removes an egg, pressing the large

end into the eye socket. In this way a large contact is made where the skin is sensitive, nearly constant in

temperature, but little below blood heat and from which the air is excluded for the time. Long practice permits

them thus to judge small differences of temperature expeditiously and with great accuracy; and they maintain

different temperatures during different stages of the incubation. The men sleep in the room and some one is on

duty continuously, making the rounds of the incubators and brooders, examining and regulating each according to

its individual needs, through the management of the doors or the shifting of the quilts over the eggs in the brooder

trays where the chicks leave the eggs and remain until they go to the store. In the finishing trays the eggs form

rather more than one continuous layer but the second layer does not cover more than a fifth or a quarter of the

area. Hens' eggs are in these trays ten days, ducks' and geese' eggs, fourteen days.

After the chickens have been hatched sufficiently long to require feeding they are ready for market and are then

sorted according to sex and placed in separate shallow woven trays thirty inches in diameter. The sorting is done

rapidly and accurately through the sense of touch, the operator recognizing the sex by gently pinching the anus.

Four trays of young chickens were in the store fronting on the street as we entered and several women were

making purchases, taking five to a dozen each. Dr. Haden informed me that nearly every family in the cities, and

in the country villages raise a few, but only a few, chickens and it is a common sight to see grown chickens

walking about the narrow streets, in and out of the open stores, dodging the feet of the occupants and passers−by.

At the time of our visit this family was paying at the rate of ten cents, Mexican, for nine hens' and eight ducks'

eggs, and were selling their largest strong chickens at three cents each. These figures, translated into our currency,

make the purchase price for eggs nearly 48 cents, and the selling price for the young chicks $1.29, per hundred, or

thirteen eggs for six cents and seven chickens for nine cents.

My project thread

Agriculture collects solar energy two-dimensionally; but silviculture collects it three dimensionally.

1

1

|

What's that smell? I think this tiny ad may have stepped in something.

Rocket Mass Heater Resources Wiki

https://permies.com/w/rmh-resources

|