5

5

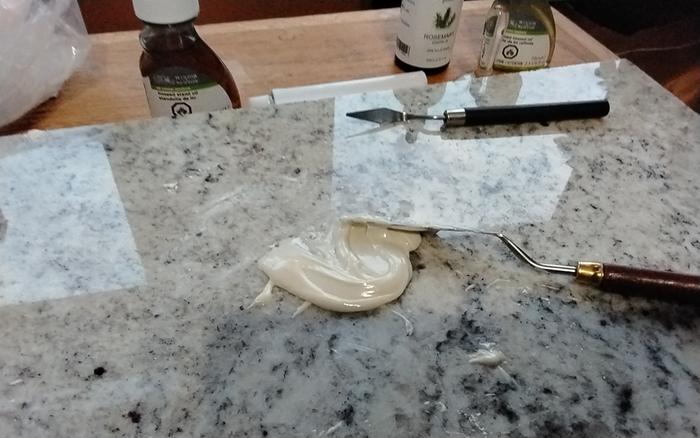

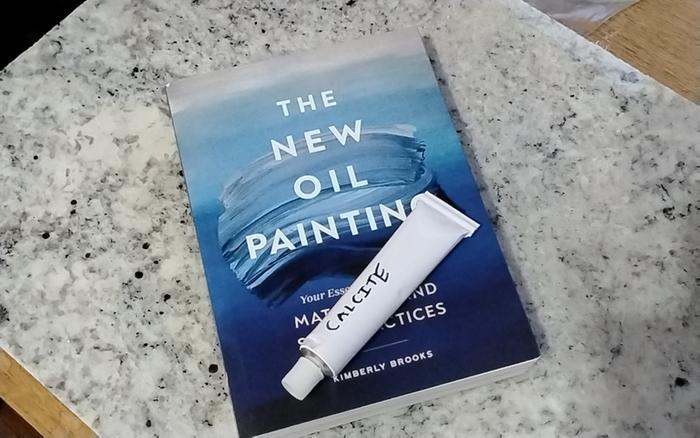

Finely ground calcite in bodied linseed oil. Use to extend paint without altering its consistency. Softer than Impasto Medium, makes colors slightly transparent allowing greater control over tints without whites.

SPOILERS

yes, I made it work, although it was a journey gathering together information from different sources to figure out what experiments to try.

5

5

Calcite is a brilliant white, fine whiting (chalk) for making grounds and adding to paint. Our whiting is dry ground from limestone deposits. Use this whiting to make chalk grounds and for adding texture and body to paints.

The finest whiting for making brilliant white chalk grounds. Our whiting is dry ground from limestone deposits in the Lucerne Valley, California. Dry grinding limestone reduces it to a powder without destroying its particle structure, which is essential in making strong chalk grounds and providing tooth on the surface of the grounds. The larger particle size of our chalk (when compared to precipitated chalk) keeps oil absorption low, which is ideal when adding it to oil paint and mediums. In painting grounds, it makes a durable surface with tooth for egg and casein tempera, distemper, encaustic, and oil paint.

Limestone (calcium carbonate CaCO3) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock that is the primary source of the material lime. It is composed mainly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate.

The Lucerne Valley limestone district contains enormous high-brightness, high-grade calcite limestone reserves. The limestone district lies in the California Transverse Ranges of Southern California. The district extends for about 40 kilometers along the north slope of the San Bernardino Mountains overlooking the Mojave Desert. About 5% (12-thousand hectares) of the San Bernardino Mountains is underlain by Paleozoic carbonate rocks. This carbonate stratigraphic section averages about 1,500 meters thick, with white high-grade calcite limestone units ranging from 15 to 30 meters thick.

Add ground calcium carbonate to oil colors and mediums to create textural and bodying qualities to oil paint without affecting the color. Ground limestone has a little color in drying oil, so it can be added to oil paint without affecting the tint of the color.

5

5

5

5

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

1

1

Whoah!! Check out this permie deal!! https://permies.com/w/homesteading-bundle?f=232

"The only thing...more expensive than education is ignorance."~Ben Franklin. "We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light." ~ Plato

2

2

Carla Burke wrote:Do you have a way to sift the calcite more finely, so you can maybe put just the grit into a mortar & pestal, to grind it finer?

Whoah!! Check out this permie deal!! https://permies.com/w/homesteading-bundle?f=232

"The only thing...more expensive than education is ignorance."~Ben Franklin. "We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light." ~ Plato

3

3

Carla Burke wrote:I don't think so? Calcium stuff is typically brittle enough to crumble pretty easily.

4

4

5

5

Comprehensive Classification of Extender Pigment Particle Sizes

Very Coarse Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: >100 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Particles retained on No. 150 Mesh (106 µm)

Descriptive Term: Very Coarse

Visual Reference: Comparable to coarse sand or table salt crystals

Pigments of this size were common in historical periods before the advent of fine grinding tools. Artists like those from the medieval and early Renaissance periods would often use pigments with very coarse particles, producing heavily textured surfaces with noticeable granularity, which enhanced certain tactile effects and luminosity in their artworks.

Coarse Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: 75–100 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Particles retained on No. 200 Mesh (75 µm)

Descriptive Term: Coarse

Visual Reference: Comparable to granulated sugar

As grinding techniques improved, pigments began to be processed more finely, though coarse pigments remained in use for specific applications. Coarse pigments are associated with visible brushwork and thick impasto techniques, often employed by painters aiming to emphasize texture and bold color.

Medium Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: 45–75 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Particles retained on No. 325 Mesh (45 µm)

Descriptive Term: Moderately Fine

Visual Reference: Comparable to beach sand

Pigments in this range are characteristic of traditional paint formulations used from the Renaissance to the 19th century. They offer a balance between texture and smoothness, making them suitable for both fine detail and broader applications. In modern artistic practice, these are still favored by those who prefer some degree of texture in their paint.

Fine Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: 20–45 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Passing through No. 325 (45 µm) and retained on No. 635 (20 µm)

Descriptive Term: Fine

Visual Reference: Comparable to flour or fine sand

Fine pigments are well-suited for techniques that require moderate texture, such as classical oil painting, fresco, and specific industrial coatings where some degree of opacity and visible brushstrokes are desired. The particle distribution in this size range contributes to a slight granularity, offering greater color opacity and enhanced surface coverage.

Extra-Fine Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: 10–20 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Passing through No. 635 (20 µm)

Descriptive Term: Extra-Fine

Visual Reference: Comparable to powdered sugar or baking flour

Extra-fine pigments are optimal for techniques that demand a high degree of smoothness and reduced texture, such as fine detail painting, precision coatings, and conservation work. Their size range allows for better pigment dispersion, facilitating thin layering and achieving more even, transparent color applications without visible grain.

Ultra-Fine Pigments

Micrometer (µm) Range: 1–10 µm

U.S. Standard Sieve Size: Not applicable; below practical sieve classification

Descriptive Term: Ultra-Fine

Visual Reference: Comparable to copier toner or airborne particles

Ultra-fine pigments are critical in high-performance applications, including photorealistic painting, digital printing, and advanced thin-film coatings. Their size enables exceptional light scattering and superior color uniformity, allowing artists to create highly transparent glazes, achieve fine details, and produce even color films with minimal surface texture. These properties make them indispensable for cutting-edge artistic techniques and specialized industrial processes.

4

4

3

3

5

5

4

4

3

3

2

2

2

2

4

4

1

1

2

2

3

3

2

2

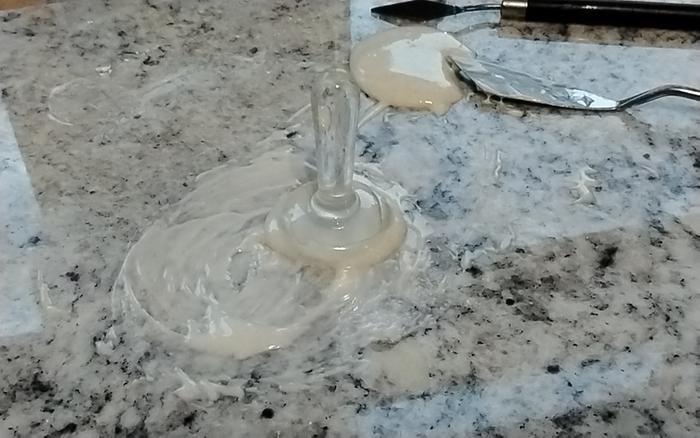

Basic putty is made from a combination of oil and stone dust. In order to produce a stronger paint film, the oil used in the putty should be stronger than the raw oil of commercial paint. This can be painter-refined organic linseed oil, and/or a semi-heat bodied oil, and can include the addition of a small percentage of thicker oil such as sun oil. There are many variations possible within this deceptively simple recipe, these result in paint with different rheologies or types of behavior under the brush.

Enter the modern conservator, armed with gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and a host of allied high-tech paint film analysis techniques which enable the detailed analysis of minute samples. In Technical Bulletin #15, (1994) London's National Gallery published an extensive article titled "Rembrandt and his Circle: Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paint Media Re-examined." The conclusion was that, while some of Rembrandt's pupils used amber varnish in isolated cases, Rembrandt himself did not. With the exception of the occasional glaze using resin, Rembrandt's paintings were made with linseed oil. The most common additions were chalk and egg. This same group of conservators and scientists, writing in the Rembrandt volume of their superb Art in the Making series, makes the same case with more paintings in more detail. This conclusion proved so controversial with Rembrandt scholars that in the updated edition of the book in 2006, the authors go out of their way to point out that they can and do find resin, it's just not in Rembrandt's paintings. The same has been true of Van Eyck research: the medium was linseed oil. The same has been true of Vermeer research, linseed oil with protein, probably egg, possibly a hide size like rabbit skin glue.

Chalk Putty

1 cup chalk

2T 72 hour walnut oil

4T 48 hour walnut oil

2T Allback boiled linseed oil

1t sun oil

A nice combination of oils for general work, good boing, dries well. Chalk putties absorb more oil but also will break if stored. This is not an issue in practice, comes back together by simple mixing.

Marble Dust Putty with BPO

1 cup Marble Dust

1t BPO #5

1T sun oil

3T+1t 72 hour walnut oil

A little loose, a little gluey, dries with an increase in depth from the BPO.

Smidge of Egg Putty

1 cup Marble Dust

4T 72 hour walnut oil

1T sun oil

1t BPO#5

1t whole egg

More set from even this amount of egg, tight detail, clean line. More egg would cause more seizure, the need for more oil to make it move. This type of putty can get a little rococo in practice, fun outside or for loose work. Can be tubed without going bad.

Prehensile Putty Underpainting

Make a dense putty with some thicker oil such as boiled or sun oil, add a small amount of a chosen color, perhaps raw sienna. Put this thinly and evenly on a panel with a large knife, carve into it to draw. Very layerable surface results. Can also be thinned with a little solvent for more control.

The first time I worked with an oil and marble dust putty in a painting I realized that it was all possible. After six years in the labyrinth of older painting technique, a large, economy size Philip Guston light bulb went on over my head. Eureka, this is it. Many mixtures, a year of trial and error later followed: once again, simplicity proved inherently complex. What follows is a description of this technology in action. It flies, quacks, swims, has feathers, webbed feet and a bill. Is it, then, a duck? This is thankfully not for the uneducated craftsman to say. Hopefully, in the best 17th Century tradition, you will simply let your own experience with the materials be your guide. This is the essence of Rembrandt's advice to Van Hoogstraten: the authentic craft develops naturally from one's own experience. So, it seems reasonable to suggest that the search should not be for the lost secrets, but for one's own practice. This is in fact easy, you start making things. At first they might not be perfect, but the information here should provide you with a running start. And, if you are cut out for this the learning curve will not be daunting, because you will realize that you are finally headed in the right direction: towards the living craft.

3

3

3

3

3

3

r ranson wrote:https://web.archive.org/web/20160314011752/http://www.tadspurgeon.com/the_book.php?page=the+book

Looks like the perfect book for learning more about calcite based mediums.

Now to find out if I can buy it within my budget. Or if it can be bought at all. Sigh.

At least the wayback machine loves me

However, while it's been a long personal labor of love, Tad has decided to stop publishing hard copies and has converted it to a pdf you may now download for free. All 566 pages of it. Which makes this an incredible gift to you. (As a pdf, you can search the entire text as needed.)

...

I post this with Tad's permission since he will be taking down the website currently hosting it at the end of October, 2023.

...

3

3

3

3

|

We're being followed by intergalactic spies! Quick! Take this tiny ad!

35 Ac. Homestead for Sale - Near Roanoke, VA – Asking: $995,000

https://thehopkinsgroup.biz/?page_id=501&et_fb=1&PageSpeed=off

|