7

7

3

3

1

1

Moderator, Treatment Free Beekeepers group on Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/treatmentfreebeekeepers/

3

3

1

1

1

1

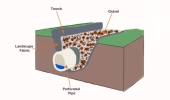

can your clay be compared to a block of forming clay as far as tight goes?Alder Burns wrote:I'm beginning to think along similar lines, with already planted fruit trees and other permanent plants, currently under drip irrigation. The soil is such a tight clay that after running the irrigation for a few hours the water starts to plume sideways along the topsoil and not stay near the plant. Suspicion led me to drill into the soil with a long drill bit near the emitters and sure enough, only 6-8 inches down the soil was bone dry, even after several hours dripping! So now I have a 2 1/2 inch diameter auger on my heavy electric drill and I'm slowly (back permitting) making a couple of deep holes around each tree, directly under the emitters, and filling these with something durable and fluffy....wood chips at least, or hair, or fabric scraps, etc.....something to keep the hole from caving in. The emitter will gradially fill these holes and water can infiltrate much deeper than before. Later I realized that Brad Lancaster and others describe a similar idea, called "vertical mulching"......

2

2

2

2

5

5

Peter Ellis wrote:Reminds me I should do some swales in my garden. Laden with mulch they will help retain moisture in my excessively drained sand.

Curious how the same technique can be beneficial in conditions at opposite ends of the spectrum.

12

12

- Tim's Homestead Journal - Purchase a copy of Building a Better World in Your Backyard - Purchase 6 Decks of Permaculture Cards -

- Purchase 12x Decks of Permaculture Cards - Purchase a copy of the SKIP Book - Purchase 12x copies of Building a Better World in your Backyard

10

10

3

3

P Oscar wrote:Instead of fighting the land, I began working with it. I allowed the “weeds” to grow—hardy pioneers like native acacias and eucalypts that required no input and no encouragement. Over time, I transplanted similar species from other parts of the property. These resilient trees became the backbone of the system.

When the rains finally returned, I chopped and dropped these hardy trees into the swales. This transformed the swales into what I call hugelswales—a hybrid of traditional swales and hugelkultur beds. Into this growing system we introduced our livestock—sheep, geese, Muscovies, ducks, chickens, horses, and cattle—by fencing them into temporary enclosures along the swales. Their manure became a key source of fertility in this evolving system.

We also began cultivating edible fungi in the hugelswales: oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) and red wine caps (Stropharia rugosoannulata). These not only contributed to yields but also helped break down woody material and enrich the soil with fungal networks.

I adopted Mark Shepard’s S.T.U.N. method—Sheer Total Utter Neglect—to establish a diverse range of fruit and nut trees. I planted widely from seed and cutting, with zero pampering. If a tree couldn’t survive, I chopped it and added it to the hugelswale as biomass. What endured was strong, well-adapted, and ultimately productive.

Our greywater is gravity-fed into the main kitchen garden swales, keeping them hydrated year-round. In winter, after leaf fall, livestock are rotated through the orchard swales. They graze the understory and fertilise the soil, essentially performing all the maintenance. ...

Filling swales with biomass prevents erosion, improves water retention and accelerates soil formation. Many of the trees we used are considered “invasive,” but I don’t view them that way. If a plant can thrive in these conditions without assistance, that’s a sign of ecological value. These plants improve the soil, provide shade and organic matter, and eventually become food for future crops. Letting so-called weeds grow is a strategy, not a compromise. They’re early successional allies in the regeneration of land and soil.

Invasive plants are Earth's way of insisting we notice her medicines. Stephen Herrod Buhner

Everyone learns what works by learning what doesn't work. Stephen Herrod Buhner

|

There's no place like 127.0.0.1. But I'll always remember this tiny ad:

permaculture bootcamp - gardening gardeners; grow the food you eat and build your own home

https://permies.com/wiki/bootcamp

|