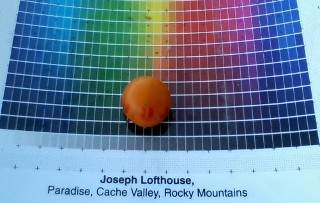

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:The third photo shows a ripe tomato from a cross between a red domestic tomato, and S. habrochaites. Andrew: If it has any seeds in it, some of them are intended for you. The fruit turned more yellow under the sunlight in the greenhouse than it did in a low-light bedroom window.

Andrew Barney wrote:4. Misidentified as Wx5 but really Solanum cheesmaniae?

1

1

1

1

1

1

Variation in mating systems and correlated floral traits

in the tomato clade

The wild relatives of the cultivated tomato provide a

great diversity in mating systems and reproductive biology

(Rick 1988). Several species, including cultivated tomato,

S. lycopersicum (formerly Lycopersicon esculentum), are

autogamous, i.e. self-compatible (SC) and normally selfpollinating

(Table 1). They bear small- to modest-sized

flowers, on mostly simple and short inflorescences; their

corolla segments are relatively pale colored, the anthers

short, and the stigma surface does not protrude (exsert) far

beyond the tip of the anther cone, all traits that promote

self-pollination and discourage outcrossing.

At the other end of the spectrum are several allogamous

(outcrossing) species. These taxa are all self-incompatible

(SI) and have floral traits that promote cross-pollination,

including large, highly divided inflorescences, brightly

colored petals and anthers, and exserted stigmas. This

group includes two pairs of sister taxa—S. juglandifolium

and S. ochranthum, and S. lycopersicoides and S. sitiens—

that are closely allied with the tomato clade, but are classified

in two other sections of the genus (Peralta et al.

2008). All four of these tomato allies have unique floral

traits that set them apart from the tomatoes: anthers lack

the sterile appendage typical of tomato flowers, pollen is

shed via terminal anther pores instead of through longitudinal

slits, anthers are unattached rather than fused, and

flowers are noticeably scented (Chetelat et al. 2009). It

should be noted that S. pennellii lacks the sterile appendage

and has terminal pollen dehiscence, but in all other respects

more closely resembles the other members of the tomato

clade.

Between these extremes are two groups of species with

facultative mating systems. The first group, which includes

S. pimpinellifolium and S. chmielewskii, is SC but their

floral structures promote outcrossing. Within S. pimpinellifolium,

there is significant variation in both flower size

and outcrossing rate. Under field conditions with native bee

pollinators, the rate of outcrossing in S. pimpinellifolium

was positively correlated with anther length and stigma

exsertion (Rick et al. 1978).

Another striking difference is that flowers of S. sitiens and S. lycopersicoides are strongly scented, whereas those of S. chilense and S. peruvianum—like all other members of Solanum sect. Lycopersicon—have no obvious odor (Table 3). The production of volatile scent compounds presumably serves to attract insect pollinators, perhaps a broader suite of bee species or other types of insects. Interestingly, the floral scent of S. sitiens, a ‘mothball-like’ odor, is noticeably different from that of S. lycopersicoides, which is more reminiscent of honey or nectar.

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:2017-04-11: Fruits ripened for the panamorous pollination project [...] I harvested about 118 seeds.

1

1

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:In a flat of seedlings which were harvested from S. peruvianum, that were inter-planted with S. habrochaites, there is one seedling that is off-type. Perhaps it's an interspecies hybrid? I'll keep watch on it, and see if other traits diverge later on.

The second photo is what is typical of the mother on the right. What is typical of the father on the left, and what looks like a plant with traits mid-way between the suspected parents in the middle.

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

William Schlegel wrote:My wild promiscuous tomato patch has progressed in my absence. My LA 1777 descended Neandermato has grown and is putting out some tight buds.

However Slow Father and Fast Father have green fruits. However fast father has a purple stripe while slow father is uniformly purple. I just checked above and that stripe can be normal for peruvianum.

Also the plant of that same Cornelio-muelleri x which survived two frosts seems yet to have formed any fruits. With its different coloration I have to wonder if it has a different father- but what or whom?

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.

1

1

2

2

Andrew Barney wrote:Joseph, how do you think you are coming along with this or similar projects as related to your original posts and original stated goals? Perhaps a hard and complex question with an equally complex answer.

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:A somewhat related side project that I am working on, is growing wild tomato species. One of them that I am working with it Solanum galapagense. The seed for it came to me with complex instructions about how I should treat the seed so that it will germinate. Instructions I suppose that were someone's idea of what conditions the seed might experience if it were eaten by a turtle...

As usual, I said, "That's nonsense! I want to select for seed that grows just like any other garden vegetable." So I merely planted the seeds without treatment. Most of them failed to germinate. But a few germinated after a long time, so I grew out the plants and collected seeds from them. A few days ago, I planted some of the collected seeds. Plants germinated in a few days. Wow! That was quick. Seems like you get what you select for. I'm mainly selecting for plants that produce seeds in my garden. And that germinate quickly.

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:The domestic-type flowering traits are highly pervasive among the offspring, By that I mean that about 90% of the offspring are reverting to domestic-type flowers rather than promiscuous flowers. It's just a numbers game at this point, so for the coming growing season, I'm intending to grow out large numbers of plants in the greenhouse in tiny pots, and selecting among them for promiscuous type flowers. The plants with promiscuous flowers can be planted together into the field. Those with industrialized flowers can be planted highly crowded into a different field, and selection among them gets to be for large or tasty fruits.

There is tremendous potential to select for fruits that are sweet, fruity, and aromatic. I might actually develop a tomato that pleases my taste buds, rather than something that is merely tolerated.

Many of these plants are huge monstrosities that seem to want to take over the garden! My selection criteria for the time being is first for promiscuity, but eventually for determinate growth habit. I'm sharing seed widely so that other people can select for what they find valuable.

The idea of using the plants promiscuity to make natural hybrids, which was suggested by John Weiland, was tried by Gilbert Fritz, who planted a Big Hill tomato surrounded by Neandermato (Solanum habrochaites). Gilbert shared seeds with me from Big Hill. I am super-excited about it. Big Hill was my first attempt at making a promiscuous tomato. It combines my life-long favorite tasting tomato, Hillbilly, with Jagodka, my earliest and primary market tomato. Big Hill has open flowers, and is fairly susceptible to cross pollination. So last night I planted about 40 seeds provided by Gilbert. By the time they are a couple weeks old, it will be obvious if any of them are hybrids, because the leaf shape of Neandermato will be dominant in any crosses. If I find any hybrids, it will save me a year on my breeding goals, maybe two if I can get a seedcrop grown over-winter.

4

4

Joseph Lofthouse wrote:A somewhat related side project that I am working on, is growing wild tomato species. One of them that I am working with is Solanum galapagense. I'm mainly selecting for plants that produce seeds in my garden. And that germinate quickly.

Eventually, I intend to incorporate the genetics of the self-compatible wild species like S. cheesmanae, S. galapagense, and S. pimpinellifolium into the auto-hybridizing project. I don't expect to work on that for a few years, but in the meantime, I am selecting among the wild species for varieties that can thrive on my farm.

By growing and sharing seeds from the wild species, I am making it easier for other people to make their own contributions to this project.I am thrilled with the collaboration that is happening regarding this project. So many clever varieties and crosses are coming to me, and saving me years worth of effort.

Andrew Barney wrote:so far i'm liking how the wild tomato wiki is forming. Should be a nice resource (if only for myself) as to what the standard leaf morphology, growing habit, fruit appearance, and other traits may be for a given species.

![Filename: pollinator-1.jpg

Description: Unknown species of bee? [Thumbnail for pollinator-1.jpg]](/t/54641/a/62787/pollinator-1.jpg)

![Filename: pollinator-2.jpg

Description: A large bumblebee. [Thumbnail for pollinator-2.jpg]](/t/54641/a/62788/pollinator-2.jpg)

![Filename: pollinator-3.jpg

Description: A small bumblebee. [Thumbnail for pollinator-3.jpg]](/t/54641/a/62789/pollinator-3.jpg)

1

1

1

1

![Filename: self-incompatible.0620181958-02.jpg

Description: Self-incompatible. Pollinators not active yet. Therefore, no fruit set. [Thumbnail for self-incompatible.0620181958-02.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79965/self-incompatible.0620181958-02.jpg)

2

2

![Filename: si-inserted-beautiful-tasty.jpg

Description: A super tasty and beautiful variety. Self-incompatible, but with an enclosed stigma. [Thumbnail for si-inserted-beautiful-tasty.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79958/si-inserted-beautiful-tasty.jpg)

![Filename: high-umami-ex-si.jpg

Description: High umami. Exerted stigma. Self Incompatible. An archetype of the project goals. [Thumbnail for high-umami-ex-si.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79959/high-umami-ex-si.jpg)

![Filename: habrochaites-3-lobes-0912181758-01.jpg

Description: Solanum habrochaites with 3 locules. Perhaps this is a back-cross with the F1 hybrid of [domestic X wild]. Exciting! [Thumbnail for habrochaites-3-lobes-0912181758-01.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79960/habrochaites-3-lobes-0912181758-01.jpg)

![Filename: wildling-2018-F2.jpg

Description: Harvested a huge amount of bulk F2 seed. Unsorted by flower type, taste, or any other trait other than darwinian survival. [Thumbnail for wildling-2018-F2.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79961/wildling-2018-F2.jpg)

![Filename: fairy-hollow-sc-wildling.jpg

Description: Fairy Hollow: The largest fruited variety. Doesn't meet any of the project goals. Fruit hollow, like a pepper. [Thumbnail for fairy-hollow-sc-wildling.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79962/fairy-hollow-sc-wildling.jpg)

![Filename: 0822181519-01.jpg

Description: That's one clump of tomato flowers! Loving the huge blossums. [Thumbnail for 0822181519-01.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79963/0822181519-01.jpg)

![Filename: tomato-beautifully-promiscuous.jpg

Description: They really know how to put on a show. [Thumbnail for tomato-beautifully-promiscuous.jpg]](/t/54641/a/79964/tomato-beautifully-promiscuous.jpg)

Western Montana gardener and botanist in zone 6a according to 2012 zone update.

Gardening on lakebed sediments with 7 inch silty clay loam topsoil, 7 inch clay accumulation layer underneath, have added sand in places.