6

6

3

3

![Filename: handspun-cotton-support-spindle.jpg

Description: The cloth in the background is handspun 2 ply silk with charkha spun cotton singles [Thumbnail for handspun-cotton-support-spindle.jpg]](/t/49607/a/31710/thumb-handspun-cotton-support-spindle.jpg)

1

1

1

1

consists of one to four rows of thick, spikes, between 10 to 30 inches long. These are usually made of metal because it's easier to construct and lasts a good deal longer than wood. The first ripple in the above link, looks more like a distaff than a ripple, but there is a lot of regional variation of tools and methods to process flax.

consists of one to four rows of thick, spikes, between 10 to 30 inches long. These are usually made of metal because it's easier to construct and lasts a good deal longer than wood. The first ripple in the above link, looks more like a distaff than a ripple, but there is a lot of regional variation of tools and methods to process flax.

1

1

1

1

Hmm, if a good set of clothes will last a minimum of five years and you get two new sets of clothes a year, then wouldn't you end up with fifteen sets before the first one wore out?

2

2

Do you know what a "clothes press" was? All I can think of to press it would be to put it under their sleeping place. I'm not sure they had mattresses when they had clothes presses, though, so I don't want to use the term "mattress". "Trews" is another medieval clothing term I've not quite got a handle on, either.

How permies.com works

What is a Mother Tree ?

Kathleen Sanderson wrote:

What is the best type of spinning wheel for working with cotton?

Kathleen

r ranson wrote:I find that drop spindles are difficult to spin cotton with. Cotton is such a short fibre and needs loads of twist, that a regular drop spindle can't put the twist in fast enough and is too heavy for the yarn. A little support spindle like this Tahkli spindle works wonders. You rest the tip in the bowl, and it spins fast. Having the spindle supported in one hand, allows the other hand to do a long draw (woolen if it were wool) which is one of the fastest ways to hand spin.

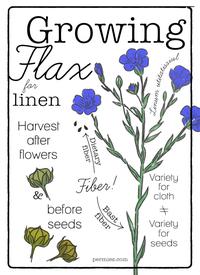

Going Green wrote:I would love to know more about the whole process from sourcing the seed to growing and harvesting

It is something I would like to have a go at, I love working with cotton so growing my own and processing it myself seems like the next step.

Nicole 😊

1

1

Kathleen Sanderson wrote:A thread for just cotton might be a good idea, though I am also interested in linen.

"Also, just as you want men to do to you, do the same way to them" (Luke 6:31)

1

1

"Do the best you can in the place where you are, and be kind." - Scott Nearing

Beth Wilder wrote:I looked but didn't find a thread just on growing cotton. Is there one now that I missed? I live in/near one of cotton's homelands and this year would like to try growing Sacaton Aboriginal Cotton (developed by the Pimans for food and fiber, related to Hopi cotton) and Davis Green (a cross between Pima cotton and a Louisiana green cotton, said to produce a longer fiber than most green cottons). I love working with color grown cotton especially. I'm going to try seeding them "when the mesquite begin to leaf out" as the Pimans reportedly did. They haven't leafed out quite yet. A couple years ago I grew some Sacaton at about the same elevation as here (abt 4,300 ft.) but nearly 4 degrees latitude north. It didn't produce copiously there, but it did produce. Embarrassingly, I haven't processed those bolls yet. I'm hoping for higher yields down here, and I'd just add those few bolls in. I'd love to talk more with folks about the vagaries of growing and processing cotton on a small scale if there's interested. Thanks in case!

"Also, just as you want men to do to you, do the same way to them" (Luke 6:31)

Xisca - pics! Dry subtropical Mediterranean - My project

However loud I tell it, this is never a truth, only my experience...

Xisca Nicolas wrote:

Cotton, linnen, hemp, nettle.... Can they be put in an order of ease/accessibility for realistic use at home scale?

Xisca - pics! Dry subtropical Mediterranean - My project

However loud I tell it, this is never a truth, only my experience...

1

1

1

1

2

2

Mandrake...takes on and holds the influence

of the devil more than other herbs because of its similarity

to a human. Whence, also, a person’s desires, whether good

or evil, are stirred up through it...

-Hildegard of Bingen, Physica

Ryan M Miller wrote:Now I'm curious how forum members build their flax processing tools since they don't seem to be readily available from any major spinning wheel manufacture as of March 2021. Can most of processing equipment be built without expensive power tools?

"Also, just as you want men to do to you, do the same way to them" (Luke 6:31)

| I agree. Here's the link: http://stoves2.com |