posted 3 years ago

Reading thru a lot of posts on Permies related to various efforts wrapped around agenda of producing hot water, it slowly began to occur to me that experience I gained in a previous life working with a steam boiler might be of some benefit here. Either to help with planning, give guys some ideas on avenues to explore, or prevent some form of catastrophic event. So what follows is a bit of hot water heat technology 101. Please accept it in spirit it is offered.

Setup: So building I worked with got it's start in life circa 1915. A 3 story residential dormitory structure, with basement. So 4 floors in total, with total floor area of about 10,000 square feet. As near as I can tell, when new it was fitted out with a coal powered live steam boiler to heat the building. Each room and hallway given one or more cast iron radiators. And 100 years later, the steam distribution system was still pumping out vast amounts of comfortable, warm, radiant heat. No complaints from residents, unless they were unable to throttle the heat down, in which case they would open windows to cool things off to livable condition. It was that good.

Along about 1960, an additional 20,000 square feet was added to building. This time, instead of expanding live steam to the new building, a hot water radiant heat system was grafted on to the steam boiler. Hot water heated by means of a heat exchanger. At some point, the coal fired boiler was replaced by heating oil fired boiler, which lasted many years before going kaput, at which time that was replaced by an AO Smith natural gas fired steam boiler. So 4 floors with nearly 30,000 sf of living area heated by a steam boiler no bigger than a large side by side refrigerator.

When I became involved in building operations, the heat system was not working right, so one of first things I did was to make contact with the professional heating guy tasked with maintaining the system. He spent several hours with me explaining how it all worked. At first glance, it looked to be only slightly more complicated than a nuclear powered submarine. But after him explaining it all, it quickly became evident that whoever had designed and built the thing was brilliant. Utterly brilliant. Once it was all patched up and working as designed, it was a thing of beauty to watch.

Operation of Steam Side: A live steam system is a closed loop pressurized system. As steam is generated in the boiler, it flows into supply pipes (schedule 40 cast iron), following a one way directional pathway. Each run eventually reaches a termination point. So from boiler source to termination point, system is under pressure. This one running at only 9 psi, which may not sound like much, but I assure you it is. Anyone who has ever purged air from a home pressure canner prior to putting the jiggler weight on knows how hot that runs at 0 PSI. Temp of live steam up to nearly 240 degrees or more.

But again, system loops dead end. To distribute steam as heat, the radiators have a supply valve. Ours fitted with normal gate valves. Crack one of those open even a little bit and you could hear the steam hiss into the radiator, at which time radiators would quickly heat up. But by heating up radiators, live steam gave up it's heat and would condense as liquid water. Each radiator has a drain in the bottom of it, which allows the condensate in radiator to flow out. It was then picked up by a return line. First radiator in the loop was start of return line back to boiler room. Return lines sloped to drain by gravity. They ran parallel to supply lines.

When condensate finally makes its way back to the boiler room it is held in a return tank. Once level in that becomes great enough a pump kicks on to pump water back into boiler to repeat cycle. It is still hot, just not as hot as the live steam side is. So not much energy needed to bring it back up to steam.

When a boiler first fires up from a cold state, everything cold, it is a slow, scary process. The boiler I worked with was controlled by a series of thermostats. Once the system was activated, the boiler would turn on or off depending on outside air temp. Ours set to fire at around 50 degrees. Once thermostats began calling for heat, boiler would fire off. It started at a low idle to get water tank and all systems warming up so as to not thermal shock anything. But at some point, it then went full blast. As the water reached boiling point and steam was beginning to form, steam would flow into cold distribution pipes, at which point it would condense and start to flow backwards toward the boiler. At some points it would pocket or pool, which created a plug in the line. One steam and pressure began to build behind those pockets it would eventually break thru, at which point it shot off down the pipe like a gunshot. This process of warming up is what creates the clanking sound in steam boiler pipes. Not good and is a horrible stress on the system, but is a normal part of the process. If it happens all the time, something not right. But once the pipes warm up, condensation in the supply side lines stops and clanking goes away and system starts to function as intended. Heat distribution handled entirely by the pressure of the steam in the supply lines. Top floors worked just as well as the lower floors. Warmest rooms in the entire building were interior utility or storage rooms where steam pipes flowed thru, but did not even have radiators. There was enough radiant heat lost from pipes to get those rooms up to 80*F or more.

Best operation of this boiler was achieved by having burners run 24/7 at a low idle. It would even out peaks and valleys. High level output kicked on when PSI dropped to around 5 PSI and returned to slow idle at 9 PSI. It would just sit there and purr and all was right with the world. Boiler was sized for climate and at no time was it not able to keep up. During really cold weather it would cycle on and off more often, but never did run full blast 24/7.

Hot Water Side: As mentioned, in new building, heat distribution was by means of hot water, heated to about 140*F using live steam from the boiler, which surrounded a heat exchanger. Remarkably the size of this was only 20 gallons of water or so. Once water was heated, it ran thru distribution loops that ran to various zones. Each floor was a zone. If memory serves there were a total of 5 of these and again, provided heat to nearly 20,000 SF of living space.

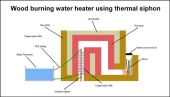

The hot water side was controlled by a system of thermostats. The reservoir in the heat exchanger had one. If temp dropped too low, a valve would open, live steam would flow in and temp would increase. Once it got hot enough, steam cut off. Each floor had a thermostat and if those were calling for heat, pumps would kick on causing water to flow heat exchanger, then on thru the loop. Instead of radiators, where heat was wanted, the hot water flowed thru a fin tube. Small at first room when water was hot, very large and end of loop where water had cooled. Since this was a 3 story building with basement, hot water was quick to rise, and cooled water flowing back to boiler room sinking, so a natural flow loop was created. (thermosyphon). The only requirement was there could be no break in the system, otherwise the syphon would break and flow stop. So critical was this that at peak of each loop, an air bleeder valve was installed on a riser to make certain the syphon was intact.

Now might be a good time to mention that all heat appliances........radiators or fin tube and warm air ducts in forced air heat systems.......are located on exterior walls directly below windows. I asked and it is done that way on purpose. Something about mixing heat from appliance with cold air infiltration from window balances heat in the room. Something to ponder.

When I first came on the scene, the hot water side had not been working right for years. The thermostats / pump connections down. But it turns out I had a past history with the building, so with a little detective work, managed to find a full set of working blueprints for the building, from which heating guy was able to located a blown transformer hidden away in a remote service panel. Once that was replaced, it all came to life and began working as designed.

But prior to that, it actually had been working.....kinda, sorta. It turns out that once a thermosyphon is established, it is actually powerful enough to overcome a lot of resistance in the line. The greater the elevation, the greater the affect. And when pumps are installed in the system, they work by enhancing suck/pull (negative pressure) on the return side. That seems to work better than trying push head pressure on the supply side. I should also point out that all our line loops were made from 3/4" lines. Cast iron or copper. These days, Pex would also work in areas you are just moving water thru, then swap to copper and fin tube where you want heat.

And one last remembrance. One heat appliance that we struggled to get working right were some fancy radiator wall devices. An electric fan pushed air thru a small radiator (like a mini car radiator). Small feed lines clogged, Radiators clogged. Fans quit working. If memory serves, we never could get about half of them to work. Low tech, straight line fin tube worked well. Fancy tech stuff bombed.

Moral to the story......despite the attractiveness and effectiveness of steam, it is a dangerous, high tech solution to heating problem. Steam boilers, real steam boilers have to be inspected by licensed heating contractors. Boilers have been known to blow up and once upon a time, a boiler had to have it's own insurance policy. At one point we had to replace two high capacity hot water heaters, and in both cases, were cautioned to keep the size no larger than 75 gallons. At some point even a commercial, high refresh rate hot water heater is viewed as a boiler and has to be inspected as if it were. Skip inspection and if anything goes wrong, insurance does not cover.

Having said that, a high capacity 75 gallon commercial hot water heater creates an incredible amount of hot water. Enough to be used as a boiler in a hot water heat system. Either by thermosyphon or by means of small circulation pump. Hot water running thru a series of fin tubes is a highly effective way to distribute heat to remote building locations. Thermosyphon will work if heat destination is elevated, circulation pumps if it is not.

Ill also mention I have seen a lot of older homes that have what appear to be upright cast iron radiators......what look like they could have been used with live steam, being run with circulated hot water systems. Am not certain about that, but if so, might be an alternative to fin tube.

With that, my fire is going dim. May go back and make some edits.

Others, feel free to set me straight or add to the discussion.

11

11

3

3

5

5

2

2

6

6

3

3

1

1

3

3

1

1

6

6

2

2

3

3

2

2