14

14

Everybody looks cool when the situation is consistently smooth. When things become horribly awkward, we then see 5% stand up and work hard on getting things to be smooth again, while 95% …. uh …. do something else.

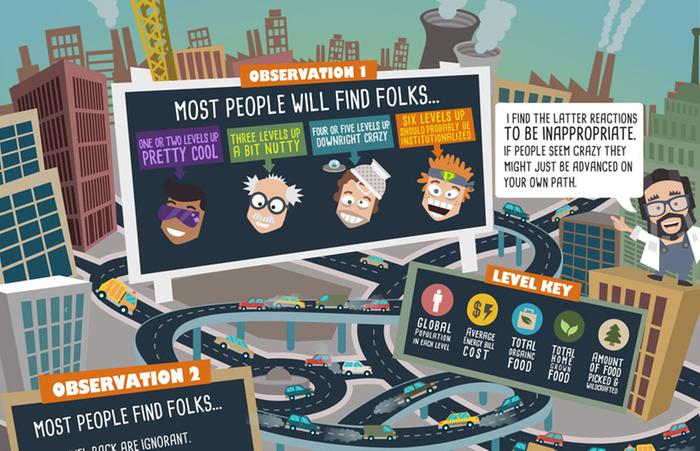

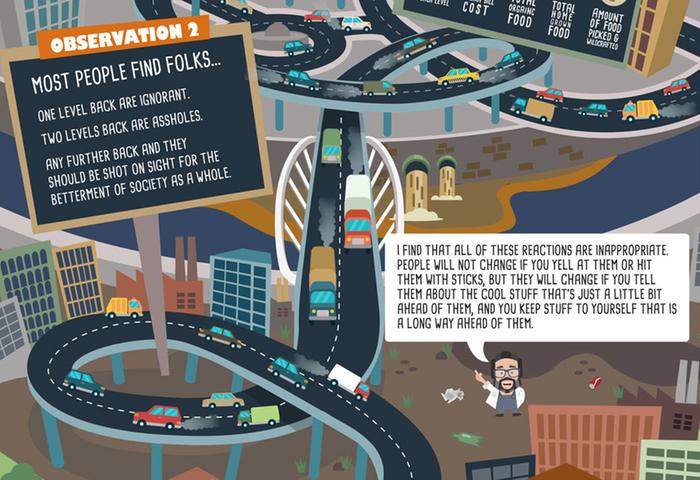

There are many schools of thought under the permaculture umbrella.

In the podcast, I start off relating a story about a woman that wrote a weekly column for the daily paper in Portland, Oregon. The column was about her attempts to become greener. One of her earliest columns was about how she went out and bought a bunch of fluorescent light bulbs. A year later, she wrote a column about how she learned that fluorescent light bulbs are an example of “green washing” and turn out to be not very green at all.

I find this to be a pretty common path. When folks get started on the eco path, they buy in to the fluorescent light bulb thing. After all, it says “eco” right on the package. And they have heard about how good it is from many sources. And then when people get a lot further down the eco path, about 1 in 100 decide that fluorescent light bulbs are awful, and then they eliminate all fluorescent light bulbs from their house.

The noteworthy thing about the columnist is that she received a mountain of ugly, hostile hate mail including death threats. The message was that these people felt that in the name of “green and eco” that advocating anything other than fluorescent light bulbs is unacceptable.

So while the “green and eco” group is usually known for peace, love, flowers, rainbows, and hugs, it seems there are at least a few that are painfully hostile. The columnist feared for the well-being of herself and her family, so she quit the column.

Most people NEED to hear their own opinion from all other people and are frustrated that they don't have the might to make it "right."

I absolutely agree with that statement. I'd even add to it: "...and are frustrated that they don't have the might to make it 'right', so instead they transform the problems unique to their brain into everybody else's problems.."

This is pretty much the root-cause analysis of social dysfunction.

I shared a link to reddit where a permaculture enthusiast replied to a comment about winning a ticket to voices and said "I'm gonna win then I'm going to go a punch Paul Wheaton in the face." I wish to emphasize that this was a person who spends lots of time in the permaculture subreddit - so I think it is fair to say that this person is supposedly a permaculture enthusiast. And checking that person's contributions to reddit you see this:

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

2

2

When TPTB take away a persons LEGAL ability to produce for themselves, then I will be a criminal and you will get to support me

When TPTB take away a persons LEGAL ability to produce for themselves, then I will be a criminal and you will get to support me

1

1

David Livingston wrote: will not such a community naturally evolve if you have enough people interested in Permaculture ?

9

9

1

1

).

).

Living in Anjou , France,

For the many not for the few

http://www.permies.com/t/80/31583/projects/Permie-Pennies-France#330873

17

17

paul wheaton wrote:There are many schools of thought under the permaculture umbrella.

2

2

Nicole Alderman wrote:

paul wheaton wrote:There are many schools of thought under the permaculture umbrella.

I felt this needed to be illustrated. It's such a beautiful quote.

Blessings,

Alana

"Things that will destroy man: Politics without principle; pleasure without conscience; wealth without work; knowledge without character; business without morality; science without humanity; worship without sacrifice." -- Mohandas Gandhi

7

7

But why have most of the people on the planet never even heard of it? Why is it that "permaculture" is not a household word?

2

2

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

-Robert A. Heinlein

Earthworks are the skeleton; the plants and animals flesh out the design.

5

5

4

4

Celtic/fantasy/folk/shanty singing at Renaissance faires, fantasy festivals, and other events in OR and WA, USA.

RionaTheSinger on youtube.

Pop-up garden/vintage+ yard stand owner.

| I agree. Here's the link: http://stoves2.com |