Angelika Maier wrote:There is no such thing as a breathable house.

Many of the traditional buildings, in many cultures, are described as being "breathable". Many modern, green buildings are also "breathable" by design. The materials are deliberately not air- or water-tight and will regulate their humidity, which changes throughout the year. I assume that's what Cameron means?

Cob is a good example of a breathable material. It will absorb water from the air during periods of increased humidity and release it when the humidity drops. This is one of the desired characteristics of cob - much like its ability to do this with heat, it acts as a buffer or a battery and ease transitions between extreme weathers (hot, cold, too wet and too dry). The change in humidity will create subtle air currents within the building and aid air exchange.

Many types of stone are also porous and will allow air and moisture to pass through them, albeit slowly. This assumed that the house is not rendered on the outside, or is rendered using a porous plaster such as limewash. Some types of stone (such as slate and granite) are not porous, however.

Modern houses usually include "trickle vents" above windows to allow continuous air exchange, preventing mold growth and the build up of formaldehydes and other unpleasant pollutants. In fact, building codes usually have a figure for a number of complete air exchanges that should take place each hour (meaning how many times ALL of the air inside a house should be replaced with fresh air from outside).

Cameron Miller wrote:

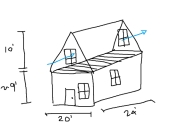

Is plywood breathable? Its wood sheets glued together, not sure what glue is used, maybe some sort of epoxy? Would this make the house not very breathable? I wont have any house wrap / moisture barriers (besides the tar paper). I want to make sure the house can breathe and the wall cavities can expel moisture to prevent mold and the sawdust to remain dry.

Plywood comes in various grades - most significantly, "marine" and regular. Marine ply uses a better quality of glue and typically has fewer voids between the sheets and, in general, is more durable and waterproof.

In general, I would say that plywood is not particulary breathable. There may be some air and moisture exchange through a sheet of plywood but I would imagine that most of that happens around the edges.

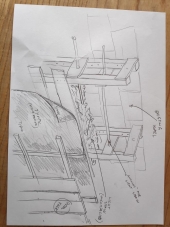

Personally, I wouldn't want to use plywood externally but that may be due to the damp climate in which I live. I have tended to build using a vapor barrier (e.g. tyvek) between my insulation and my breathable cladding material (e.g. heavily-overlapped, durable timber planks). I feel this allows any moisture that makes its way into the insulation to evaporate out (via the vapor barrier and through the gaps between the cladding boards). I do intend to use plywood to internally clad the shed I am currently building as I don't expect much moisture to end up inside the building - and water on boots, for example, that does make its way inside will be able to drain via the holes between the floorboards.

2

2

2

2

1

1