From

Wikipedia:

Nukazuke (糠漬け) is a type of Japanese preserved food, made by fermenting vegetables in rice bran (nuka), developed in the 17th century.

I'm currently tending my fourth pot of Nukadoku and thought it might be worth writing about here.

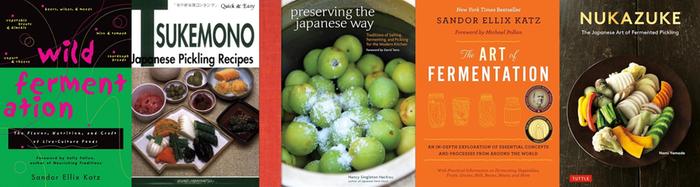

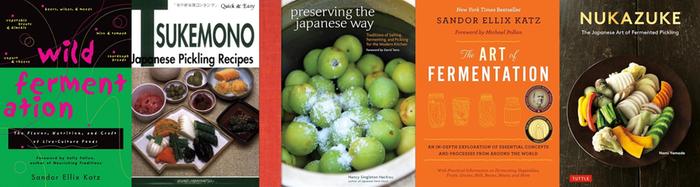

I first read about Nukazuke in Sandor Katz' excellent

Wild Fermentation about 20 years ago. It took a while to get the stuff together, but I'm pretty sure my first pot of nuka started in 2005. As my enchantment with nuka blossomed, I started seeking out more information, but it was hard to come by in English. These five books, along with a very small amount of short essays and forum discussions that I've found online, have guided my experimentation:

I started writing the next paragraph and decided I should define my terms. I think these are exactly as Sandor spelled it out in Wild Fermentation, so probably credit to him, but I'm using these Japanese terms (without actually knowing any Japanese) like this:

nuka - rice bran

nukadoku - nuka + water + salt + a diverse colony of microbial life + various other ingredients (mustard, ginger, garlic, chiles, turmeric, kombu, etc.

nukazuke - pickles made by immersing produce in nuka for a few hours, days, months, or depending on who you believe in the case of takuan, years

Each time I start a new pot of nukadoku (so far, at least), I religiously put in the work to keep it living for 6-36 months and then let it die due to inattention. We'll see how this one goes. Keeping an active nuka-pot requires mixing it with your hand daily -- twice is better and more or less required if you live somewhere hot. I don't, but I do have two reminders each day set to help me stir it. And you also have to keep cycling produce through the nukadoku to keep stimulating the mix of microbes with fresh colonists. And you have to manage the moisture and salt level -- adding rags or dried beans to take up too much water, adding water when it gets too dry, adding salt when your pickles start to seem not salty. And you have to consider the putrifaction impulse. As long as you're mixing it daily and moving produce through the matrix, this isn't much of a problem. But sometimes I get lazy or something just goes wrong, and it picks up a rank funk. At that point I try things like adding mustard powder and garlic. And you're constantly removing nuka...you try not to, but it's unavoidable. It's even probably a good thing because the nuka is full of nutrients that leave the pot in the pickles you eat, so sometimes you add more...dry if the pot is too wet, with water if not, and maybe with salt.

And all the variables that I'm mentioning are dials you can turn, to experiment, or just to suit your taste. In

Wild Fermentation, Sandor instructs us to make a pretty wet nukadoku. Other sources told me that it should be dryer and when he wrote the

Art of Fermentation, he corrected himself, relying on

Preserving the Japanese Way for more info. The recent

Nukazuke book is somewhere in between those two extremes. And to make things more complicated, the wet nuka made following Sandor's original instructions made better pickles than the drier nuka following Nancy Singleton Hachisu's instructions...at least for me, the small number of times I've done this.

So anyway, I want to show you how I started my current batch.

First, I got out my kioke that's been wrapped in plastic for four years because we moved house and things slip away, cleaned it up, and soaked the wood. If you're trying this, you'll probably use a ceramic crock or something -- that works fine and is easier.

Then I got some nuka. I know people have used wheat bran because it's easier to find in the US, but I've had bad luck with that and prefer to use real nuka. I get it mailorder from an organic rice farm in Vermont:

https://rhapsodynaturalfoods.com/home/nuka/. I've found that a lot of sources tell you to toast it, but the most recent book says that's only needed if you're not using it fresh. Toasting nuka in a big wok takes forever and makes a mess, so I'm trying this batch without, and just freezing any dry nuka that I'm not using.

And I added salt and water. I used six lbs of nuka in this batch and 327g of salt. And I added a couple big sheets of kombu which kind of broke up during the mixing process. Then I stirred in water until I could just barely squeeze a drop of water from a fist-full of nukadoku.

This begins the boring part. You need to spend a couple of weeks inoculating the nukadoku. I took bits of kale and mustard greens and just whatever was handy from the garden and mixed it in each day, removing yesterday's leaves to enter the compost. After a couple weeks of that, there was a good head of funk and I started adding veggies: pickling cukes, raddish, chiles, cloves of garlic, cauliflower, chunks of napa cabbage. But I'll add anything! Many things pick up a little flavor in a few hours and almost everything is unbelievably funky if left for a week.

It's a lot of fun introducing people to nukazuke but sometimes it takes some convincing for them accept that it's food.

My most common way to eat it is to slice it thin and have it with brown rice, maybe with shoyu, maybe with toppers like sesame and nori flakes. But we also put fat-sliced cucumbers on burgers or just eat it alone as a snack. You can tell from this next series of pictures that I've left the pickles in progressively longer in three batches. Things get more and more dehydrated and funky over time.

One thing I'm not too sure about is whether this really qualifies as a preservation technique. I don't really use it that way. I make stuff, I eat stuff. When I make a five gallon pot of kimchi, it takes us six months to get through it and it never spoils. But most sources discussing nukazuke seem to want the produce out of the nukadoku after a few hours and then I'm not sure what I'd do with it to store it. Can I pack it in a jar and put it down-cellar? I guess I'll have to try that and get back to you.

17

17

4

4

4

4

8

8

6

6

4

4

5

5

1

1

1

1

3

3

2

2

4

4

2

2