13

13

6

6

6

6

Gardens in my mind never need water

Castles in the air never have a wet basement

Well made buildings are fractal -- equally intelligent design at every level of detail.

Bright sparks remind others that they too can dance

What I am looking for is looking for me too!

4

4

Ask me about food.

How Permies.com Works (lots of useful links)

2

2

5

5

2

2

4

4

11

11

3

3

3

3

8

8

5

5

Mandrake...takes on and holds the influence

of the devil more than other herbs because of its similarity

to a human. Whence, also, a person’s desires, whether good

or evil, are stirred up through it...

-Hildegard of Bingen, Physica

8

8

10

10

"We're all just walking each other home." -Ram Dass

"Be a lamp, or a lifeboat, or a ladder."-Rumi

"It's all one song!" -Neil Young

6

6

I love your cloth label, can you share where you get these from? I'm a spinner and weaver also, and am always looking for a better solution! Thank you so much, I'm really glad this was well supported, you guys have put so much work into it, and it's AWESOME!!!

I love your cloth label, can you share where you get these from? I'm a spinner and weaver also, and am always looking for a better solution! Thank you so much, I'm really glad this was well supported, you guys have put so much work into it, and it's AWESOME!!! 1

1

8

8

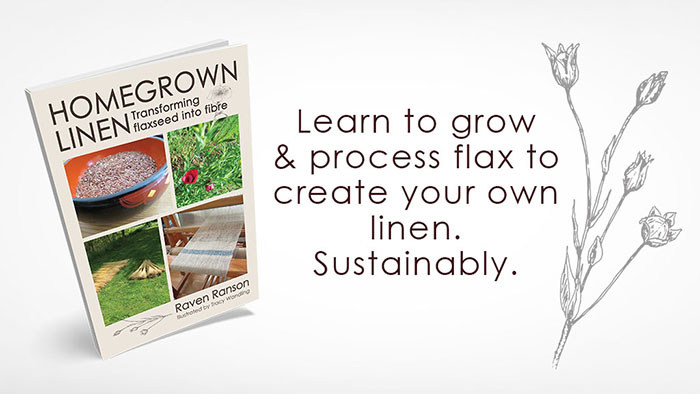

Linen Landrace

By Raven Ranson

first published on Permaculture Magazine North America Website

“Organic Fiber Flax Seed. Plant in well-drained soil, full sun, after last frost date, 100 days to harvest.”

These were the words on the envelope that started it all. A manilla affair, 2 inches by 4. A white sticker label with planting instructions and a picture of a little blue flower. Immediately I was in love. Finally, I had found a plant fiber to fall in love with. Traditionally grown in less than perfect soil, planted at the tail end of winter, or even late fall… wait a moment, the packet says plant after last frost date. Something’s wrong.

Linen is the textile made from the fibers extracted from the stem of the flax plant. The process is somewhat labour intensive, but the resulting fabric can’t be matched for durability and breathability. Stronger when wet, cool to the touch, linen makes excellent summer clothing and the perfect base layer in winter. This is the same plant that produces linseed and flaxseed – Linum Usitatissimum. The variation in the different cultivars is surprisingly diverse. Flax grown for seed production is often squat, has many branches and focuses most of its energy into reproduction – as many big seeds as possible. Fiber flax, on the other hand, is delicate and lanky. Very few seeds; what it does have are usually small. The phylum, the circulatory system in the stem, becomes the textile – this bast fiber runs the length of the stem, from root to tip. The longer the stem, the fewer the branches, the better the cloth.

(Traditionally fiber flax is blue, but there are almost 200 different kinds of flax, with a great variety in flower color and shape.)

Around the world, many people are rediscovering the joy of transforming flax to linen. It was from one of these groups, The Flax to Linen Group of Victoria, BC, Canada, that I found my inspiration. Fascinated by the history of the plant, I’ve gathered up little tidbits of tradition and ideas on how it grows, but lacked the courage to try it. Finding a group of people who shared my interest was a true blessing; however, it’s surprising how different modern day flax growing is to historical accounts – especially planting times. At first, I thought this was because the tradition had changed, so I experimented by planting flax at different times of the year, only to discover that they were right, this variety does grow best when planted around the last frost date. However, this is also about the time our summer drought starts, so planting flax at this time of year means irrigating it for the first 50 or 60 days of growth (it takes about 100 days from germination to harvest). Crops that need watering do not fit into my plans for the farm. What I need is a different variety of fiber flax.

Easier said than done. Gathering together all the seed catalogues and resources I could find, that year there were only three sources of flax seed, two of them out of stock, the third was already growing in my garden. As interest in growing linen increases, there are more flax suppliers; even still, it is an area with room for a lot of expansion.

It was about this time that I first discovered landrace gardening and the work of Joseph Lofthouse. Most of the seeds we buy are a specific cultivar, they have predictable and uniform traits; landrace seeds are more diverse. For example, we know that Moneymaker tomato all produces red fruit, of a uniform shape and size, with lots of juicy seeds, grow well in greenhouses &c. A landrace tomato will share one or two traits, maybe they are cold tolerant and ripen early, but unlike a cultivar, a landrace has a great deal of genetic diversity. Some of the fruit might be yellow, others green with stripes, some red. Some large, some small… you get the idea. Landrace = genetic diversity. Genetic diversity leads to resilience.

(6 different kinds of flax, each a different shape. The taller ones are more desirable for flax production, but the shorter ones are generally more bee friendly and hardy in the garden. The goal is to combine these resilient traits with the taller shape.)

Inspired, I decided to create a landrace flax. My linen landrace would be a lot like the flax of my history books: frost tolerant, growing tall during the rainy season and drying down during my drought. My landrace would thrive in marginal soil and need almost no weeding as it would grow when many of the weed seeds are still in their winter slumber. To produce the finest fiber, the stems would grow tall and there would be no branching which weakens the fiber. With these qualities in mind, I bought a packet of every and any flax that remotely resembled these qualities, planted them about 8 weeks before our last frost date in the hope that natural selection would rid me of any frost intolerant varieties. I was rewarded with a great diversity of shapes and sizes of plants, as well as a gorgeous selection of flowers. My plan is to encourage promiscuous pollination, inviting bees to transfer pollen between the varieties, mixing up the genetics and giving me something new to select from.

That was the original plan. Get the bees to do the work, grow and promiscuous pollinate the flax, save the seeds, grow again. Do this for two or three years to build up a joyful diversity, then start roguing (removing) the short and branchy plants so that I select only the plants that will produce good fiber. The landrace should be mostly stable in about 5 or 6 years. If only it were that simple.

Alas, it wasn’t until recently that I discovered that flax has only a 3% chance of crossing by insect*. Only 3% chance of promiscuous pollination? This isn’t much better than a regular garden pea, a notorious self-pollinator, which is usually declared to have a 1% chance of cross-pollinating. However, quite often these numbers come from industrial agriculture, which discourages insect activity. If they have no bugs, the chance of cross-pollinating via insects is minimal. In an organic setting, cross-pollination for peas can be as high as 25%. So maybe, my 3% for flax is in an industrial setting. Oilseed is the most valuable flax crop for industrial agriculture and maybe the studies were done on this variety of flax, not the lesser used fiber flax? It’s possible, but until I have more data, only a hypothesis. The more I read, the more I learn. There is, however, another source of knowledge, far more useful than books and interweb.

The first principle of permaculture – my personal favorite – is to observe and interact. I have 7 different varieties of flax in my garden at this moment. If the books have taught me anything, it is that numbers, like ‘pollination by insect’ vary drastically from place to place. I am growing flax on my farm, the best source of information I have is to observe my flax. So I do. And wow, do I learn some exciting things!

The flax flowers are only open for a few hours a day. Some wake up with the sun, others laze closed until lunch, and one variety is a true lazy bone and waits till the heat of the day, about 2pm, to wash the sleep out of its eyes and show it’s petals to the world. In the early morning there seem to be fewer pollinators interested in flax, but come early afternoon, there are always bees or wasps buzzing between flowers. The insects seem to avoid some varieties, but obsess over others. Why is this I wondered? On closer inspection, I noticed that the flowers the insects avoid have their anthers wrapped tightly around the style (pollen making parts wrapped around the pollen-receiving parts) which prevent contributions from foreign pollen. The flowers the insects are attracted to have their anthers spread apart as if welcoming the bugs with open arms. These are also the flowers that are open in the early afternoon. I suspect these flowers are more likely to cross-pollinate. Unfortunately, only one of these varieties is the right shape to be a fiber flax – fortunately, one of these varieties is the right shape to be fiber flax, meaning that I am already ahead of the game and am starting with some desirable traits.

Another challenge/opportunity will come when I start to save seeds. If I was growing flax for seed, I would treat it as like beans and peas, collect every seed, toss them together, and that would be the end of it. However, seed production is not what I want in my landrace flax. If I were to just collect all the seeds in one big bucket, then plants that produce lots of seeds would be more prominent. I would be inadvertently selecting for seed production. Instead, I have a decision to make. Do I save seeds from each type of flax, then plant an equal number of each plant? Or do I plant more of the ones with fiber friendly characteristics? Or perhaps, I want to focus on promiscuous pollination, which at this stage in the project, do not produce the best fiber. I could plant twice as many bee friendly flax as I do the other varieties. Or I could keep the seeds from each plant, separate, then plant “x” number of seeds from each ‘mother’ plant and observe the sibling groups.

Whatever my choice, it will affect the direction this project takes. I find this thrilling. Imagining my perfect plant, then working with the plants to actualize my dream. It might be a success and in a handful of years, I’ll have my linen landrace or perhaps things might lead in a completely different direction. It may even happen that nothing comes of this and the bees refuse to help create crosses. Even that won’t be an absolute failure. It has been an excellent opportunity to practice the first principle: observe and interact.

Breeding a landrace or one’s own variety of vegetables opens up a whole world of possibilities. It needn’t be flax, it could be artichokes or zucchini, or anything in between. Unlike professional plant breeders who must meet market demands, which aren’t necessarily the qualities that small producers desire. Amateur plant breeders don’t have to ship our produce long distances or harvest by machine. That leaves us free to focus on qualities like taste, thriving in local conditions, and most importantly, beauty.

* These numbers are from Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties by Carol Deppe.

11

11

Sourdough Without Fail Natural Small Batch Cheesemaking A Year in an Off-Grid Kitchen Backyard Dairy Goats My website @NourishingPermaculture @KateDownham

13

13

Learn more about my book and my podcast at buildingabetterworldbook.com.

Developer of the Land Notes app.

12

12

My little flax/linen garden bed! It's pretty small, but it's something. It's seeded with flaxseeds from Raven's kickstarter! I'm hoping I learn a lot this year, and so I can scale up next year!

Is that little bitty flax that I spy? I hope so!

(The fence is over it to keep my ducks from eating all the seeds...something I realized the day after I planted it. Hopefully they didn't eat too much of it in that time!)

3

3

3

3

Whoah!! Check out this permie deal!! https://permies.com/w/homesteading-bundle?f=232

"The only thing...more expensive than education is ignorance."~Ben Franklin. "We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light." ~ Plato

3

3

5

5

Lord Bless You!

We cannot direct the wind, but we can adjust our sails...

3

3

Visit Redhawk's soil series: https://permies.com/wiki/redhawk-soil

How permies.com works: https://permies.com/wiki/34193/permies-works-links-threads

1

1

4

4

Jay Angler wrote:I'm curious Raven - how long before the 'last frost' date in your region, are you now able to successfully plant your Landrace flax seed?

3

3

5

5

6

6

7

7

Like my shiny badges? Want your own? Check out Skills to Inherit Property!

2

2

He whai take kore noa anō te kupu mēnā mā nga mahi a te tangata ia e kōrero / His words are nothing if his works say otherwise

3

3

|

Uh oh, we're definitely being carded. Here, show him this tiny ad:

Our PIE page has been updated, anybody wanna test?

https://permies.com/t/369340/PIE-page-updated-wanna-test

|